This is the second part of a three-part story by historian Alan Roberts into the escape from Japan of German prisoners who ended up in Skipton.

FRITZ Sachsse, the senior German Officer at Raikeswood Camp, was a remarkable man.

He did not arrive at Skipton until June 1918 when the war was almost over. Astonishingly he had first been captured in China at the very start of the First World War and had embarked on an amazing, but ultimately unsuccessful escape from prisoner-of-war camp in Japan that took him well over halfway round the world.

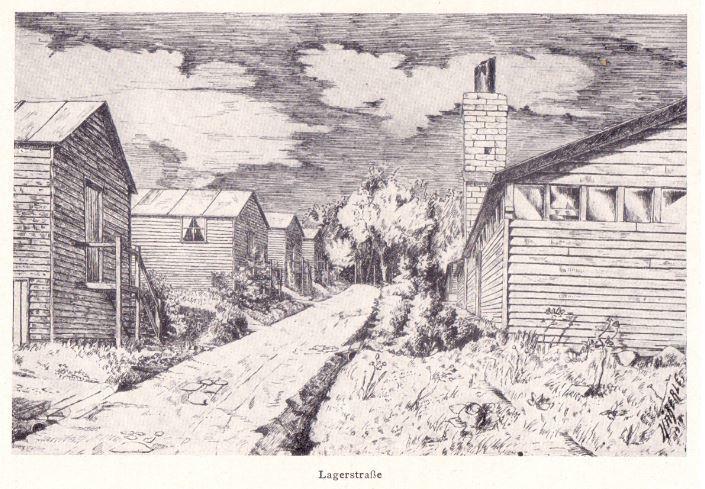

Sachsse arrived in Skipton in the nick of time. Defeat by Britain was bad enough, but in spring 1919 Spanish flu was to devastate the inmates of Raikeswood Camp. Forty-seven officers and men would die from the disease from just 683 prisoners. As senior German officer, Sachsse had to lead the tributes to the deceased comrades. Furthermore the officers were able to fund the construction of a monument in Morton Cemetery near Keighley. Meanwhile peace negotiations were dragging on in Versailles, and the Skipton prisoners rightly believed that they were being held as hostages until a treaty was signed and implemented.

Sachsse had daily meetings with the British commandant of the camp. He also had the difficult job of maintaining discipline among several hundred, young, frustrated and hot-headed officers who wanted to be anywhere but behind the barbed wire. ‘Kriegsgefangen in Skipton’ the 300-page book written by the German officers about their life in Skipton is another testament to Sachsse’s achievements.

By December 1915 Sachsse had escaped from Japan and had crossed to mainland Asia by ferry. The German community in Shanghai was extremely hospitable, until one day a Chinese man approached him on the street and said, ‘Good morning, Captain. We all know you are here.’ If his friends knew that, then so did his enemies. It was time to move on. The plan was to cross neutral China and head for Afghanistan where a military commission was encouraging Afghanistan to become completely independent from Britain and take Germany’s side. Not for nothing was this called a ‘world’ war!

Sachsse and fellow naval officer Herbert Straehler studied the scant information available in preparation for their journey west along the well-established ‘Silk Road’. They set out in January 1916 in the depths of the Chinese winter travelling a comparatively short distance by train before they had to revert to traditional Chinese transport by palanquin. Sachsse described this as two sturdy pieces of wood hung on either side of one mule at the front and another one at the rear. For passenger accommodation a crude hut was constructed from straw matting which was mounted on the wooden beams connecting the animals. The German officers now wore Chinese clothing: fur caps, long quilted trousers and sheepskin-lined coats with long sleeves extending over their hands. They soon abandoned Western-style food – it took too long to prepare – and ate whatever food was readily available. Mule-drawn carts were preferred to the palanquins and later stages were completed on horseback. Conditions were difficult with frozen ground and delays due to snow drifts. Once a cart fell through the ice of a frozen river taking a mule with it so only its head was poking above the surface.

By March the two German officers had reached the town of Jiayuguan at the western end of the Great Wall of China. Then there were sandstorms, and the sight of thousands of camels grazing on the steppes before their caravans continued their eastward and westward journeys. A few days later they were to set out across the Gobi Desert – an unending sea of sand and stones where distant mountains and trees proved to be mere illusions.

The rumour was that a group of Germans and Turks was travelling west to incite the local population in Xinjiang into revolt. Accordingly a large group of very curious people greeted Sachsse and Straehler as they entered one particular town. The escape was clearly no longer a secret. Russia was at war with Germany and determined to stop them. The authorities in Beijing therefore ordered the local Chinese officials or ambans to deter Sachsse and Straehler from continuing their journey. Their military escort was removed in the town of Karasahr. Any onward travel would be at their own risk. Anything could, and probably would happen, once they left the security of the town.

Reluctantly the two German officers were forced to retrace their footsteps. It was now April and they had been travelling for three months. Recrossing the Gobi Desert it was getting quite warm, but still bitterly cold at night. Furthermore an uprising caused them to take a more northerly route which involved a journey by boat and raft down the Huang He or Yellow River. This was no pleasure cruise: they faced fearsome rapids and a whirlpool which caught their vessel and caused it to circle several times before releasing it.

They returned to Shanghai in June almost six months after they had originally set out. The German ambassador agreed they had been right to turn back. There had been no realistic hope of reaching Afghanistan and possible safety. After a journey of more than 5000 miles and still in China, how did they end up in Skipton?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here