BEFORE great the meeting of the Airedale Writers’ Circle (AWC) in January five members had circulated their poems and prose for other members to critique.

Praise is always welcome but constructive criticism is more useful: are readers hooked into reading on past the title and first paragraph or verse? Are there errors of spelling or punctuation, or phrases that stumble?

The “rule” is that poems are best read out loud for others to fully appreciate their rhythm, rhyme and messages.

Martin Walker’s Eau Naturelle is an exception, as it relies for its impact on words which sound similar – and so rhyme – but are spelt (markedly) different, for example the verse which relies on the place-name “Belvoir” being pronounced “beaver”: “When lost in the Forest of Belvoir/ I spotted a golden retrelvoir/ Whose feverish Berks/ (Which frightened the lerks)/ Sounded just like an opera delvo.

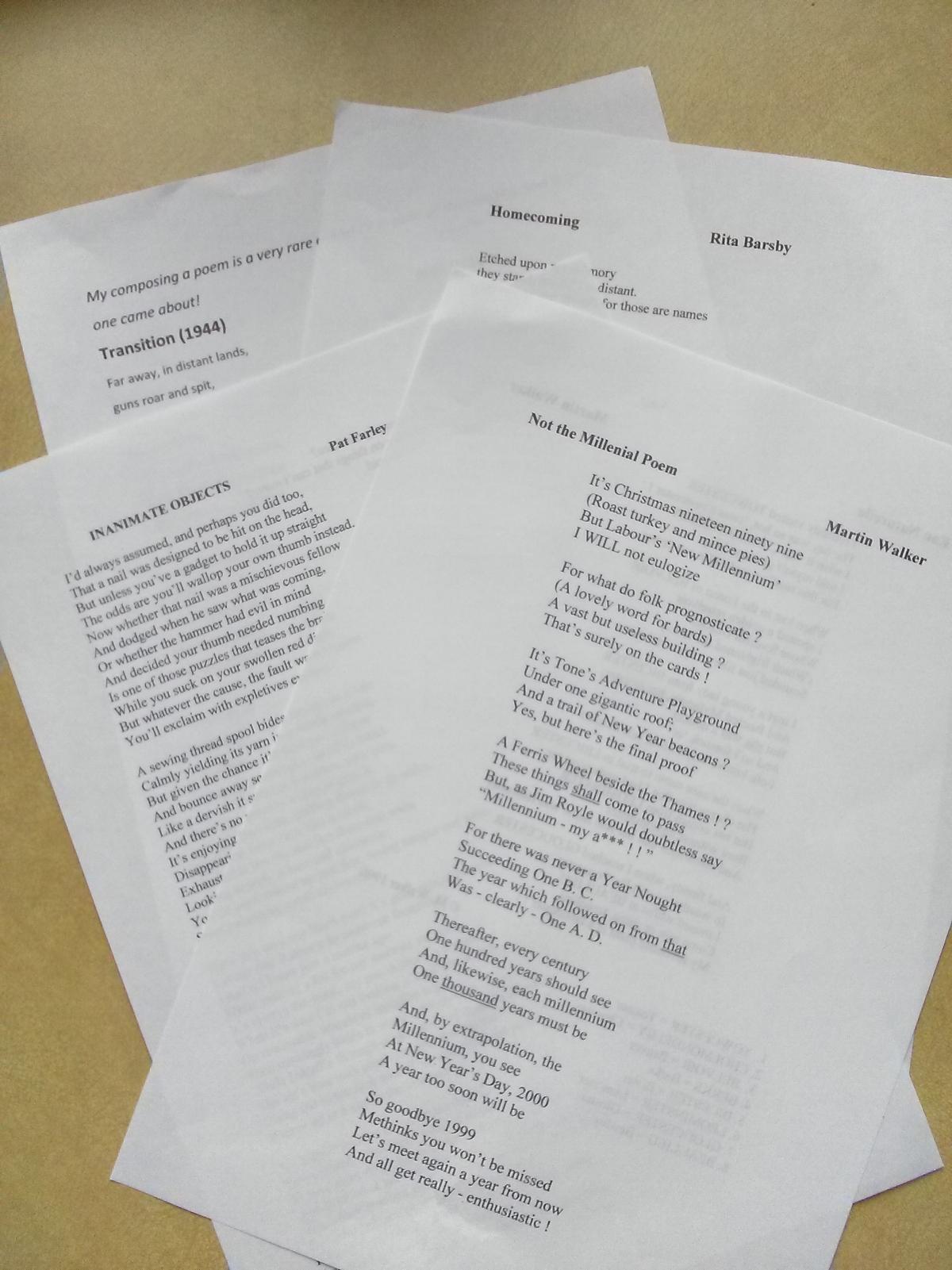

Martin’s other offering was his Not the Millennium poem.

Seems that we celebrated the start of the new millennium a year too early as “There was never a Year Nought/ Succeeding One BC/ The year which followed on from that/ Was - clearly - One AD”, so it took until 1.1.2001, and not 1.1.2000, for 2,000 years to have passed since 1.1.01.

Rita Barsby’s sentimental poem Homecoming gloried in depicting the scenic, hilly landscape near her home in Skipton and her “joy beyond all joy/ that leads me ho

A more distant setting featured in my poem Transition (1944).

A photograph of a crofter ploughing with horses on the Hebridean island of Iona provided the contrasts of war – “Far away, in distant lands/ guns roar and spit”– and that tractors would soon be displacing horses into “munching apples and lolloping free.”

John Roberts’s prose extract was of part of the first chapter of his novel set in 1613 Lancashire.

Its opening lines of “He must not laugh. Must. Not. Laugh” certainly hooked us into reading on... into a description of a meeting of the God-fearing Brethren of Separatists whose forbidding pastor “stared at each [of the congregation] in turn, who duly bent their heads for they had all surely sinned”.

The text’s strong characterisation made us all eager to read the finished book.

Pat Farley then entertained us with Inanimate Objects, her marvellously humorous poem which deals with the mischievous antics of, for example, sewing spools that spontaneously unwind (reel adolescents!), and pens that hide – hence her conviction that every object “has a mind of its own”.

We finished with my draft foreword for a memoir of my life as a GP. Both my father and grandfather were GPs too but never committed to paper any of their experiences. That this seems a shame motivates me to pen mine.

Our offerings elicited the feedback wise writers – however talented – need to hone their work.

All are welcome to come to our next meeting at 7.30pm on February 12 at the Sight Airedale building, immediately behind Keighley Library, in Scott Street. We will be discussing our favourite animal-related poems and prose.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here