CONTROVERSY currently surrounds the future of Keighley Library – and others across the district – as Bradford Council seeks to make cuts.

The local authority is looking to make savings of more than £1 million from its libraries and museums budget. Some campaigners fear closures. The council denies there are plans to shut any sites, but does warn that staff cuts and reduced opening hours are likely.

Fourteen days of strike action by library and museum staff district-wide in the battle against the cuts began last week. The Unite union, which represents around 50 employees in the service, is spearheading the action.

As the row over future library provision continues, we take a look back to bygone days.

Keighley has long had libraries.

A Braithwaite diarist makes obscure references to one as early as 1794 – it stocked “odd magazines and Shipwreck of Antelope & Town & Country Mag for 1786 and Binns Catalogue for 1789” – and by 1823 bookseller Robert Aked was running a circulating library from his shop in Low Street.

But it was the Mechanics’ Institute, founded in 1925, which formed a serious comprehensive collection of books “for mutual instruction” of its members.

By the 1830s, the Keighley Mechanics’ Institute library boasted more than 800 volumes of philosophy, history, natural history, geography, arts and sciences, and poetry and literature, but not yet novels, the reading of which founder John Farish considered “only another kind of mischievous excitement”!

Towards the end of the 19th century the new Keighley Borough Council started discussing the provision of a public library and the idea was given dazzling impetus through the friendship of local educationalist and mill-owner Sir Swire Smith with Andrew Carnegie.

In 1899, the wealthy Scots-born American industrialist offered to contribute £10,000, thereby making Keighley’s the first proposed Carnegie library in England, although one at Cockermouth in Cumbria managed to actually open ahead of it.

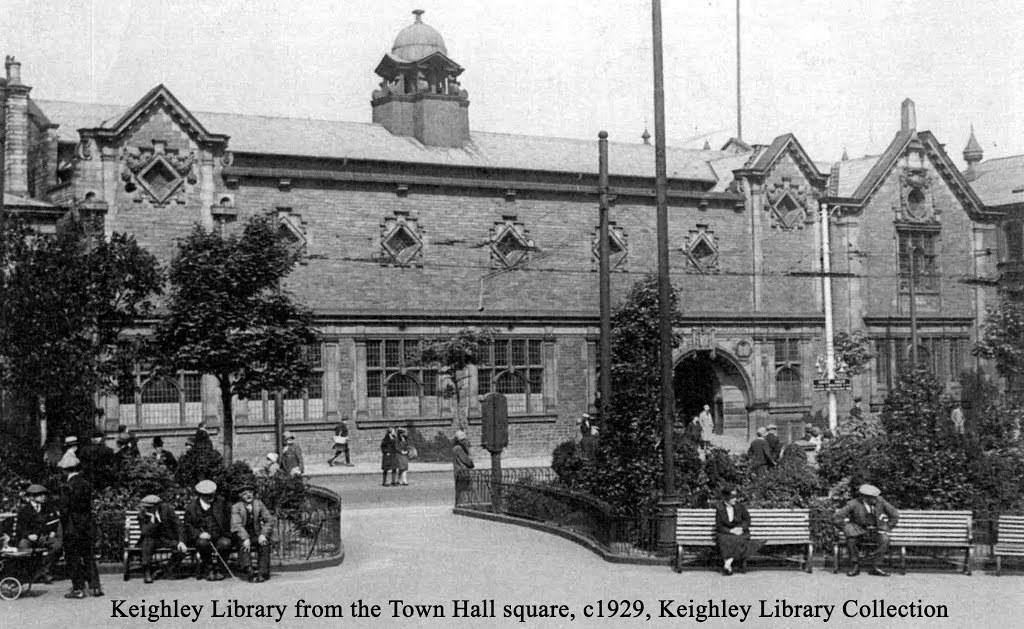

Design of the library was open to competition, and one submitted by McKewan and Swan of Birmingham was chosen. Both were young architects – Arthur McKewan was 30 in 1901, and James Arthur Swan was 27.

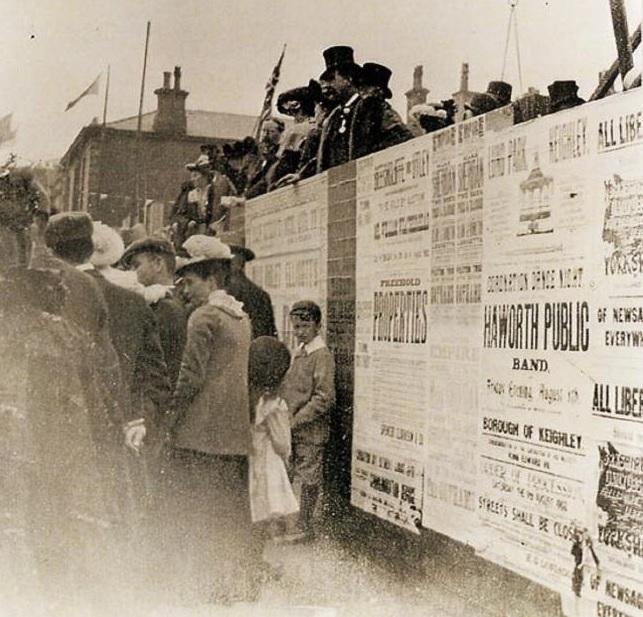

Advantage was taken of the festive atmosphere of the 1902 Coronation Day to celebrate the memorial stone-laying ceremony for Keighley’s budding Carnegie library.

Dignitaries watched a tableaux procession make its way along North Street. Sir Swire Smith performed the stone-laying ceremony.

Presented with a silver trowel and oak mallet, he “spread the mortar, and laid the memorial stone in a workmanlike manner”.

In his speech, he related the conversation which had led to Mr Carnegie’s generosity: “Mr Carnegie said ‘What is your population?’. I replied about 42,000. ‘Why,’ he said, ‘£10,000 would build you a library’ to which I replied ‘Yes it would’. Without more ado he said, ‘Well, I will give you a library’.”

The Stars and Stripes were flown from a flagpole in Mr Carnegie’s honour.

Keighley Public Library, officially opened by the Duke of Devonshire in 1904, took over both the librarian and an initial 13,000 book stock from the Mechanics’ Institute.

During its first year, it attracted nearly 3,000 borrowers, endearingly recorded by their occupations and including 520 “married women, spinsters, juveniles, etc”, 261 mechanics, 199 clerks and book-keepers, 134 schoolmasters and teachers, ten postmen, ten policemen, seven journalists, six photographers, two window-cleaners and a rag merchant!

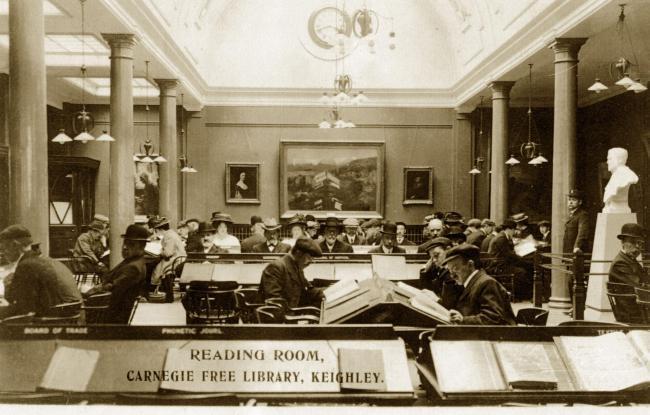

Its reading room could seat 150 and took 20 daily newspapers, 80 weeklies, 63 monthly magazines and two quarterlies.

A reference library followed in 1912, and a children’s library in 1929.

Librarian Robert Summerskill Crossley, who had accepted the post “for the time being”, stayed for 42 years, coming back out of retirement during the Second World War.

He was succeeded in 1946 by the late Fred Taylor who – in partnership with the late Alderman John Stanley Bell, the enthusiastic chairman of a Keighley Libraries, Arts and Museum Committee – further developed extensive lending, reference and archive collections. And 1961 saw the addition of a purpose-built children’s library.

By the early 21st century, however, despite an expensive refurbishment and the emergence of a pre-eminent local studies department, a fashionable policy of replacing books with screens, while encouraging non-readers to use libraries as drop-in centres, had largely undone the efforts of previous generations.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel