Here, Robin Longbottom recounts the life of a soldier who went on to become mine host of a Keighley tavern...

TODAY, the Reservoir Tavern – at Calversyke Hill, in West Lane, Keighley – is surrounded by the urban sprawl of the town and has industry to one side and housing to the other.

However, when it was built in the early 1830s, it was still remote from Keighley and stood in an open landscape surrounded by fields.

Across the road was a small reservoir, which stored the town’s water supply and after which it was named.

The inn catered not only for the small community living in cottages at Calversyke Hill but also for the many travellers who used West Lane as a route over the moor to Cross Hills and Kildwick to avoid paying tolls on the turnpike road through Steeton and Eastburn.

Its first innkeeper was a retired soldier called Christopher Ingham.

Former soldiers were often popular choices for landlords, being sociable, tough and well used to handing out discipline.

It is not clear who actually owned the Tavern, but he was no doubt suitably impressed when Ingham applied for the tenancy and produced his certificate of discharge from the army. Section five, concerning ‘character’, stated “his general Conduct as a Soldier has been good – in service thro’ the whole of the Peninsula War & at Waterloo”.

No doubt without hesitation the owner granted him the tenancy and the choice was a good one as he remained the landlord for over 30 years.

Christopher Ingham was born in Colne in Lancashire in 1787 and was a weaver by trade.

His life had changed when Napoleon Bonaparte, having conquered most of Europe, closed its ports to British commerce in 1806. As a consequence of Britain losing its European markets, there was a slump in the textile trade and many thousands were thrown out of work. Therefore, on March 25, 1809, Ingham – described as 5 feet 7 inches tall, with light brown hair, a fair complexion and grey eyes – joined the 1st Battalion of the 95th Rifles for a period of unlimited service.

The 95th Rifles, made famous by Bernard Cornwell’s books which followed the career of the fictional Richard Sharpe, were an elite regiment of light infantry. Unlike other British regiments they wore a green uniform, which was the first attempt at camouflage. They were armed with the Baker rifle, as opposed to the much less accurate smooth bore musket used by other regiments. These elite riflemen were trained as sharp shooters and often sent forward of the frontline of battle to pick off the enemy, officers in particular.

By the close of 1809, Private Ingham was with the Duke of Wellington’s forces in Portugal and engaged in the Peninsula War.

In September 1810 he fought in his first action at Bussaco, where French forces were defeated. After wintering in Portugal he was back in action again at the Battle of Fuentes de Orono.

In 1812, Private Ingham was at the sieges and capture of the Spanish fortress towns of Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajos and then at the defeat of the French at Salamanca outside Madrid. Over the next two years – as the army made its way north to France – he fought at the battles of Vittoria (June 1813), the Pyrennees (July 1813) and Orthes (Feb 1814). By April 1814 he was with the British forces at the gates of Toulouse in southern France, when Napoleon abdicated and surrendered to the British.

However, the war resumed when Napoleon returned to France from captivity in 1815 and the 95th Rifles were once again in action against the French in Belgium.

Private Ingham’s battalion fought in the very first engagement with the enemy at Quatres Bras and two days later they played their role in the final defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo.

Ingham remained with the regiment for a further 14 years and was finally discharged in 1829, after 20 years of service.

He returned, briefly, to Colne where he married Betty Heap in 1832 before moving to Keighley.

In 1816, all soldiers who had participated in battles during the Waterloo campaign were awarded a silver medal and subsequently known as ‘Waterloo Men’.

This act caused much resentment among the veterans of the Peninsula War and there was a popular movement to have medals struck to honour them.

However, it was not until 1847 that it was finally approved and Christopher Ingham was granted his with nine clasps, each naming a battle that he had fought in.

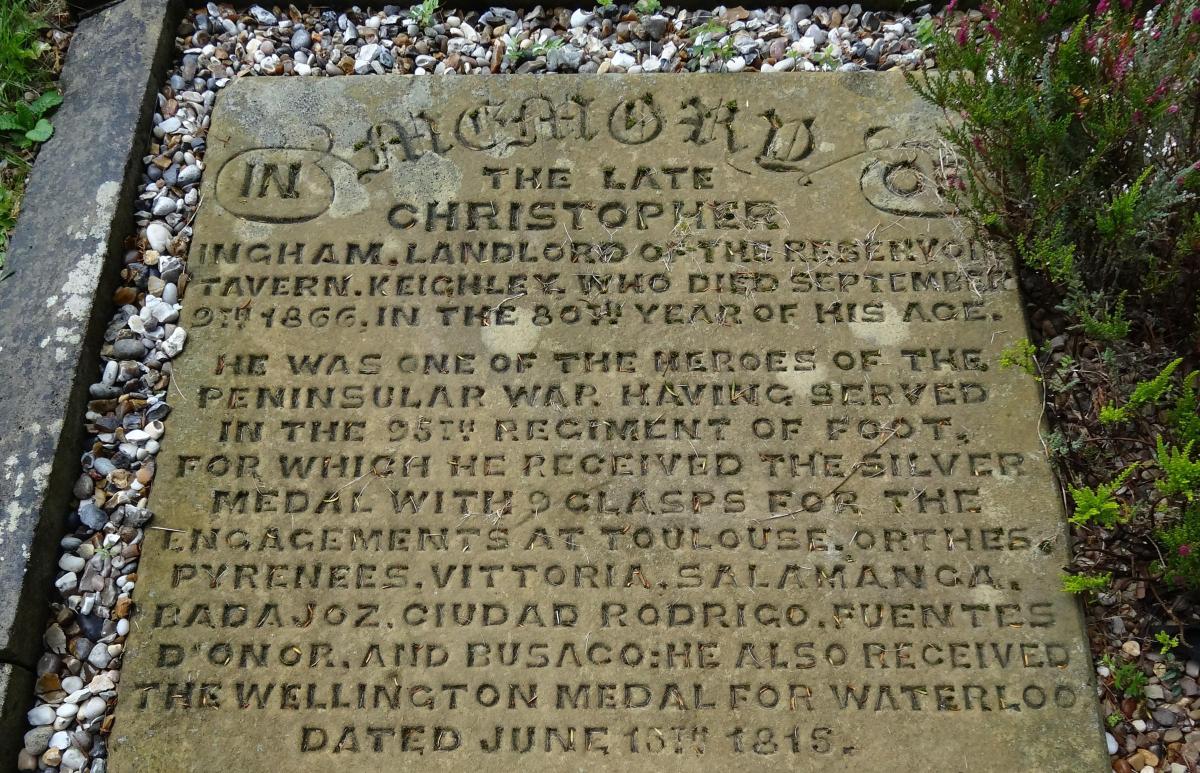

Ingham died in 1866 in his 80th year and is buried in a quiet corner of Utley Cemetery.

He was one of the last heroes of the Peninsula War and his tombstone proudly lists all his battle honours.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel