Here, Robin Longbottom examines how firms played their part in supporting British industry during its dependence for almost two centuries on leather

“THERE’S nothing like leather” was once a popular saying used to dismiss ideas for change or innovation.

However there was some truth in the statement, as for nearly 200 years British industry was dependent upon it.

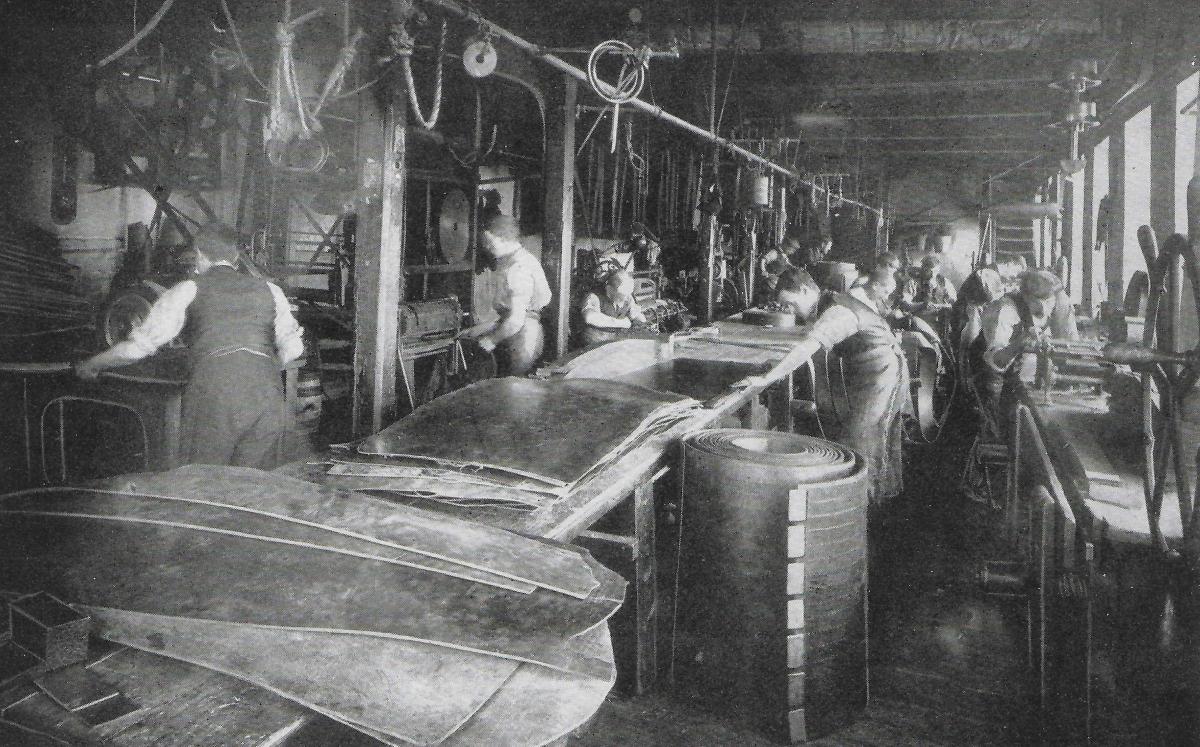

Leather belts and straps were once the only means by which power could be transmitted from waterwheels, steam engines and later electric motors, to machinery in both heavy and light industry. Surprisingly, they were still in use into the 1960s.

Early in the Industrial Revolution, mills usually bought cured hides and made their own leather belts.

But as industry expanded, mills gradually turned to specialist manufacturers to meet their needs and from the mid 19th century the tanners and curriers (leather finishers) of Keighley began to concentrate on manufacturing transmission drive belts.

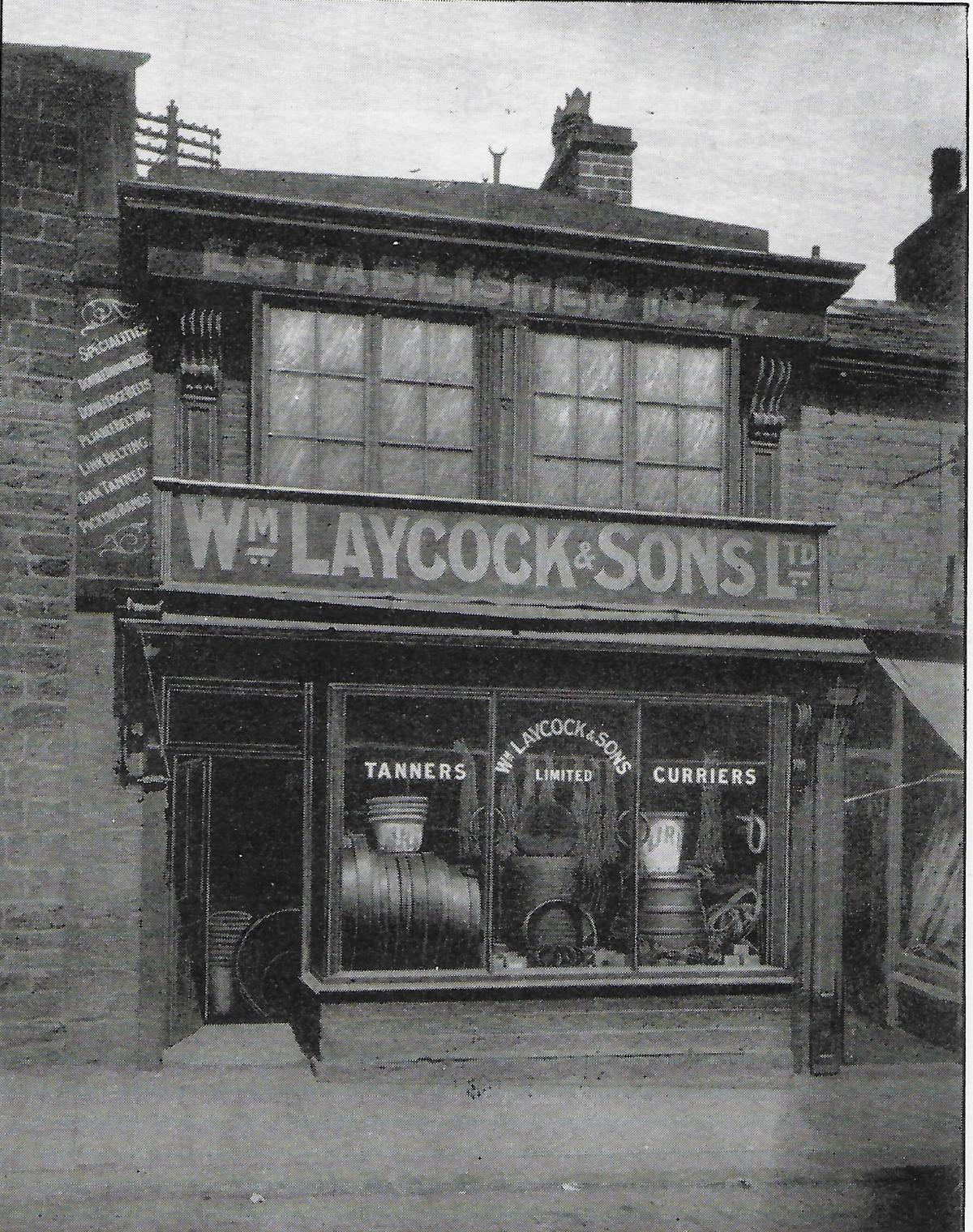

Three such firms were prominent in the town in the 19th century and early 20th century – James & Thomas Whitehead, Isaac Foulds and William Laycock and Sons.

William Laycock started in business in 1847 and he bought ready tanned hides, dressed them and made them into machine belting.

In 1890 the business took over the long-established Bolton Road Tannery in Silsden and was able to boast that they “take raw hides from the butcher, tan them in the good old-fashioned way, curry them and prepare them by their own special processes and supply them direct to the customer.”

Manufacturing was a long process. The hides were first soaked in lime pits and then taken to the ‘beam-house’ where a workman scraped the hair off with a two-handled knife (the hair was sold on to be used to bind plaster for houses etc). Any remaining flesh was also scraped off and the poor-quality edges were cut away. The hides were then suspended in tanning pits containing a mixture of water and oak bark liquor.

Once tanned, a hide was known as a butt and these were finished by the currier who treated them with tallow and oils to make them supple and then wet-rubbed them to give them an even thickness.

The butts were then ready to be made into transmission drive belts.

Short belts to drive machines were known as single belts. They were little more than a long endless leather strap connected from a pulley on the drive shaft to one on a machine. If the operator wanted to stop the machine he simply knocked the belt from the drive pulley onto one next to it that just spun on the shaft, hence the saying “I’m knocking off now”. More substantial ‘double edged’ belts were stronger and used to connect power between the actual drive shafts in the mill or factory.

The biggest belts manufactured were double, or primary, belts which ran directly from the power source to the principal drive shaft.

The leather was cut from the butt so that it ran lengthways down the spine and the lengths were placed flesh side together then cemented, pegged and stitched together with either copper wire or waxed thread.

Laycock’s catalogue for 1902 contains a number of testimonials. John Whittaker’s mill at Nelson had a belt 88 feet long and 32 inches wide, which had been transmitting power to 1,270 looms for 16 years. Holmes & Pearson, iron founders, of Keighley, stated that its drive belt was 168 feet long by 30 inches wide, had been running for 13 years and was still giving “satisfaction in every respect”.

William Laycock & Sons continued in business until 1968 when its Queen Street Works were demolished to make way for the new shopping centre.

Both Laycocks and Whiteheads sold out to Charles Walker & Co Ltd which in turn was taken over by Habasit (UK) Ltd, which now makes synthetic belts for the food industry.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here