Part 2 of Alan Roberts’ story of Lieutenant Emil Jakob Wommer. A young German PoW who would perish in hospital at Keighley in 1919.

WOMMER had been orphaned at the age of 15. His sister ran the village pub and her husband farmed an adjoining smallholding. He had risen through the ranks and lacked the wealth, education or privileges enjoyed by so many of his fellow officers.

Following his capture Wommer was sent to a camp at Colsterdale near Masham which had originally been built for navvies building reservoirs to supply much-needed water to Leeds and West Yorkshire. Used by the Leeds Pals as a base for training, the camp was later converted into a prisoner-of-war camp for German officers.

The captured German officers had been plucked from the battlefield in whatever they happened to be wearing at the time. Support was provided by their German comrades when they reached their designated camps. Unfortunately Colsterdale was becoming overcrowded so the most recent arrivals were transferred to the new camp at Skipton. Wommer arrived there on January 21, 1918.

Just two short letters survive from Wommer’s stay in Skipton. They are written on pre-printed forms and would typically consist of around 200 words. Space was at a premium. In June 1918 Wommer writes that his long trousers have arrived, but his German field-grey tunic has not reached him. The butter and honey had turned to liquid. The bread had been reduced to crumbs. His family might have more luck in the winter.

A small amount of land belonging to his sister and family had been sold. The price had seemed quite good. In the meantime could his family send him some money? He asks for his books to be sent to him, but not in any parcels containing food. He sends his best wishes to his sister’s young children and asks God to bless and support the fatherland. By this time the German Spring Offensive had stalled, and Germany was facing a bleak future.

The final surviving letter written by Lt. Wommer was written just after Christmas in 1918. The last letter he had received from home had been written in October, a month before the signing of the Armistice which effectively signalled Germany’s defeat. The German prisoners were remarkably well informed and regularly received copies of national and regional newspapers including The Times, Daily Mirror and Yorkshire Post. Wommer learnt that the Kaiser had abdicated and gone into exile in Holland. Two different German republics had been declared in Berlin on the same day!

Wommer guesses that a recent parcel had been sent after the Armistice; things might not be so bad after all. His homeland, the heavily industrialised Saarland, was due to be occupied and administered by French troops. He writes that Germany will have to endure some very difficult weeks. It was, he maintained, like the desecration of something held sacred. He did not realise that those weeks would turn into many long years.

Emil Jakob Wommer was admitted to Morton Banks Hospital in late February 1919. He would die just three days later. The cause of death was influenza followed by streptococcal pneumonia. The flu pandemic had a devastating effect on otherwise healthy young people. Their immune systems could become so overactive that they could attack the organs of the body resulting in death within a few short days. Forty-seven officers and men out of a total of 683 held at Raikeswood Camp would die in the flu pandemic.

The victims were buried at Morton Cemetery near Keighley. The German officers paid for a suitable memorial to be erected in their honour. In the 1960s the bodies were exhumed and reburied in the German Military Cemetery at Cannock Chase in Staffordshire. The Skipton victims lie buried in a well-tended cemetery along with nearly 5000 servicemen, merchant seamen and German civilians from two World Wars.

Wommer had done well to be promoted to become a commissioned officer. He did not have the ‘connections’ enjoyed by so many of the officers at Raikeswood. His family had been smallholders. Compare this with submarine commander Lafrenz whose family were allocated no fewer than 200 Russian prisoners of war to work his family’s estates on an island off the north coast of Germany.

Would Wommer have returned full of ideas and aspirations from mixing with young men from many different backgrounds, or would he have returned to the harsh toil of agricultural life? A photograph taken on the occasion of his sister’s golden wedding celebrations in 1960 is almost timeless. His sister and husband are in the centre of the middle row.

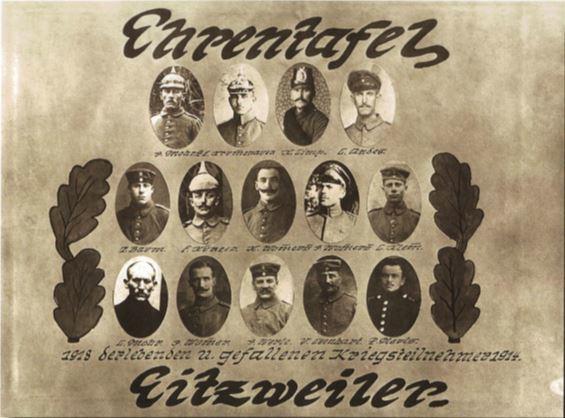

In the tiny village of Eitzweiler both survivors and victims of the conflict were remembered on a table of honour. More recently the local history society has erected a plaque listing the names of the fallen. The plaque remembers the death and suffering of many millions of people in war and is a timely call to peace to the descendants of those who survived.

Letters written from Raikeswood Camp are extremely rare so Wommer’s letters have become a veritable treasure trove!

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here