Robin Longbottom examines how a long-forgotten trade was pivotal to Keighley’s birth as a manufacturing centre

IN 1789 Richard Hattersley, his wife and family arrived in Keighley from Ecclesfield, near Sheffield.

Although history records him as a 'general blacksmith', the skills that he brought with him from Sheffield were far superior to those of the men working in basic wrought iron.

He was a whitesmith, a trade now largely overlooked and forgotten. The whitesmith worked in what was known as white, or bright, metal – better known as steel. Hattersley was a specialist smith who introduced skills to Keighley that ultimately led to the foundation of the engineering companies that were to become world leaders in the machine making and machine tool industries.

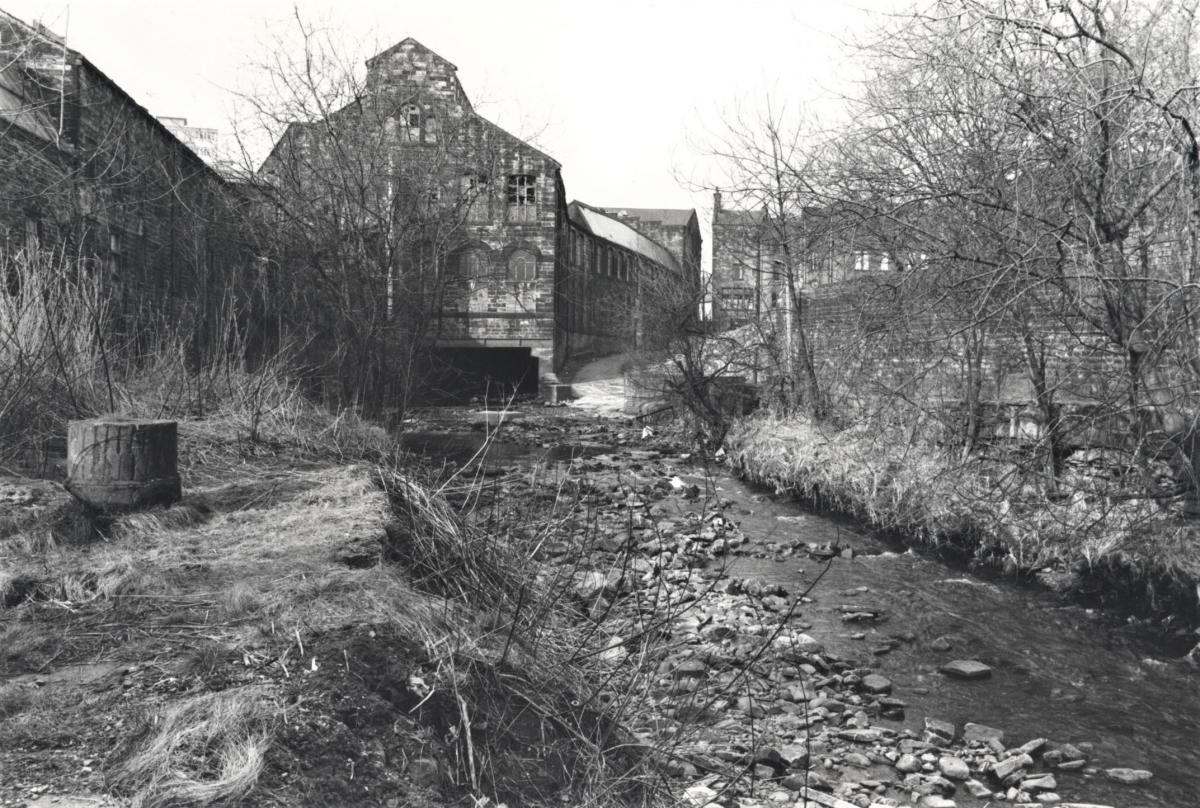

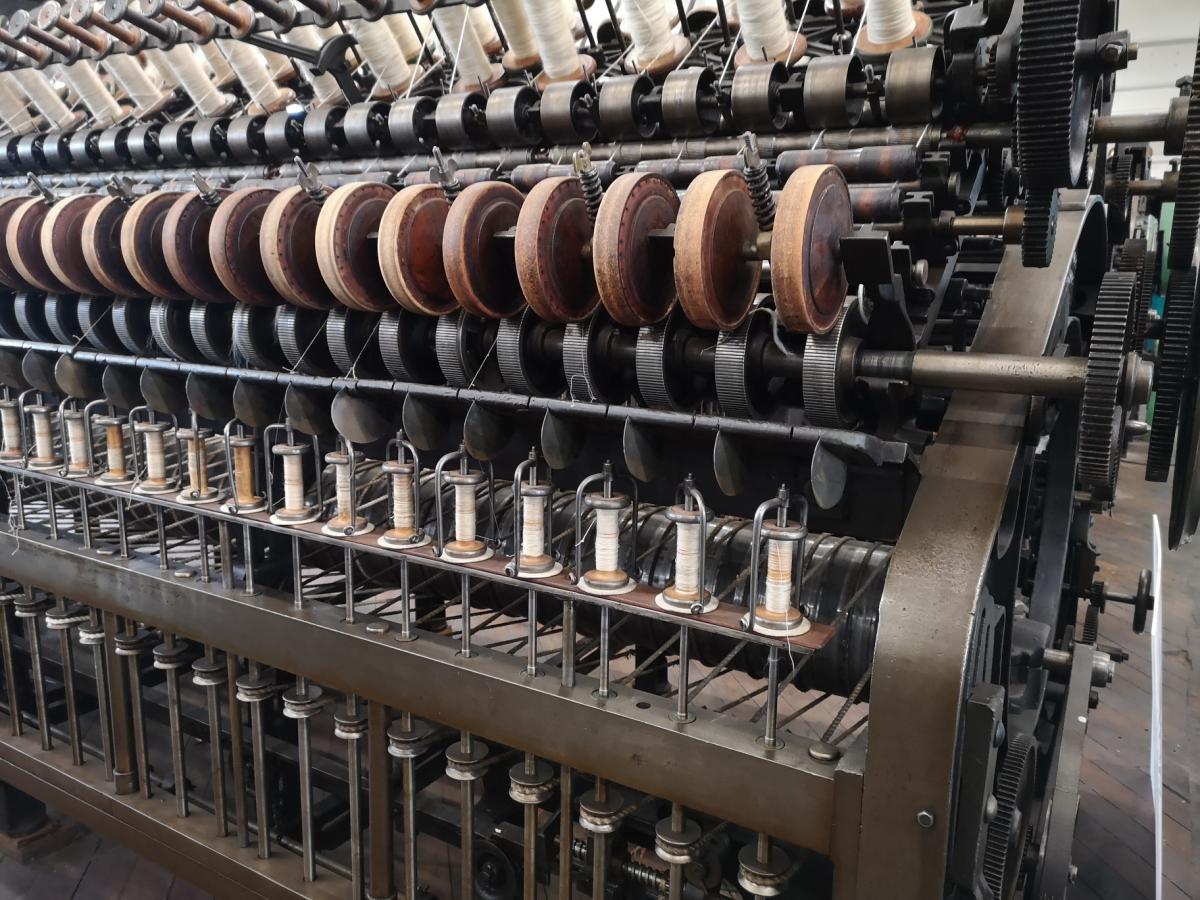

By 1793 he had set up in business at North Brook Works, off Bridge Street, in a former cotton mill that took its power from the North Beck. He probably bought forged steel bar from Kirkstall Forge at Leeds, which by then was linked to Keighley by the Leeds and Liverpool Canal. Although he did general smithing, he began to specialise in making rollers, fliers and spindles for spinning machines in the cotton, worsted and flax industries. Spinning machines – known as frames – had two pairs of rollers, each a short distance apart. The front pair ran faster than the rear and as the fibre was drawn through, it was stretched out, and then a twist was finally put into it by the flyer as it was wound onto a bobbin supported on a spindle.

Hattersley's surviving workbooks show that in his early years he only made small numbers of rollers, spindles and fliers but from 1800 he was producing them in sufficient quantities to build multiple machines. He employed both skilled whitesmiths, including himself and his sons, together with semi-skilled men known as filers, or vice men, who cut and shaped steel by hand with files – and iron turners, who worked at his water-powered lathes. He actively sought work and a surviving diary entry reveals that he, or one of his sons, often set off on horseback seeking orders from the mills of Yorkshire and Lancashire.

Other whitesmiths followed Hattersley to Keighley and by the early 1800s a total of seven are recorded in the town. However, within a generation the records show that the number had risen sharply to almost 50. One of these was William Smith, a clockmaker who had periodically worked on spinning machinery and occasionally bought spindles, fliers and rollers from Hattersley. He recognised the important role played by the whitesmith and apprenticed all his five sons into the trade. In 1816 he is recorded for the first time as both a clockmaker and a whitesmith. By 1822 he had established the firm of William Smith & Sons specialists in the manufacture of spindles, fliers and rollers for the cotton and worsted trade and was in direct competition with Richard Hattersley & Sons.

After the death of Richard Hattersley in 1829, his son George turned the business over to making worsted power looms whilst William Smith & Sons went from whitesmithing to making complete worsted spinning frames.

By the mid 1850s the records show that the term whitesmith was falling out of use. These skilled men were being absorbed into the town's new machine making industries and became known as mechanical engineers, or simply engineers. For the next hundred years Keighley was to be a leading manufacturing town for spinning frames, power looms, machine tools and other machinery.

The foundation of these industries can be traced back to Richard Hattersley and the whitesmiths who came to the town in the late 18th century. And up to the 1970s, every engineer in Keighley started his apprenticeship sitting at a vice shaping a cube of steel with a file just as the whitesmiths had done almost two centuries earlier.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel