THREE Keighley artists were attending the Royal College of Art in London when the First World War broke out in 1914.

Although only Hugh Spencer and Thomas Shackleton died in action, like them George Demaine became a casualty of war.

Silsden Mann historian Colin Neville, who runs the local art history website notjusthockney.info, reveals the three men’s varied responses to the’ Great War’.

Hugh Manning Spencer was born 1890 in Keighley; his father, Charles, was a local blacksmith in the family business.

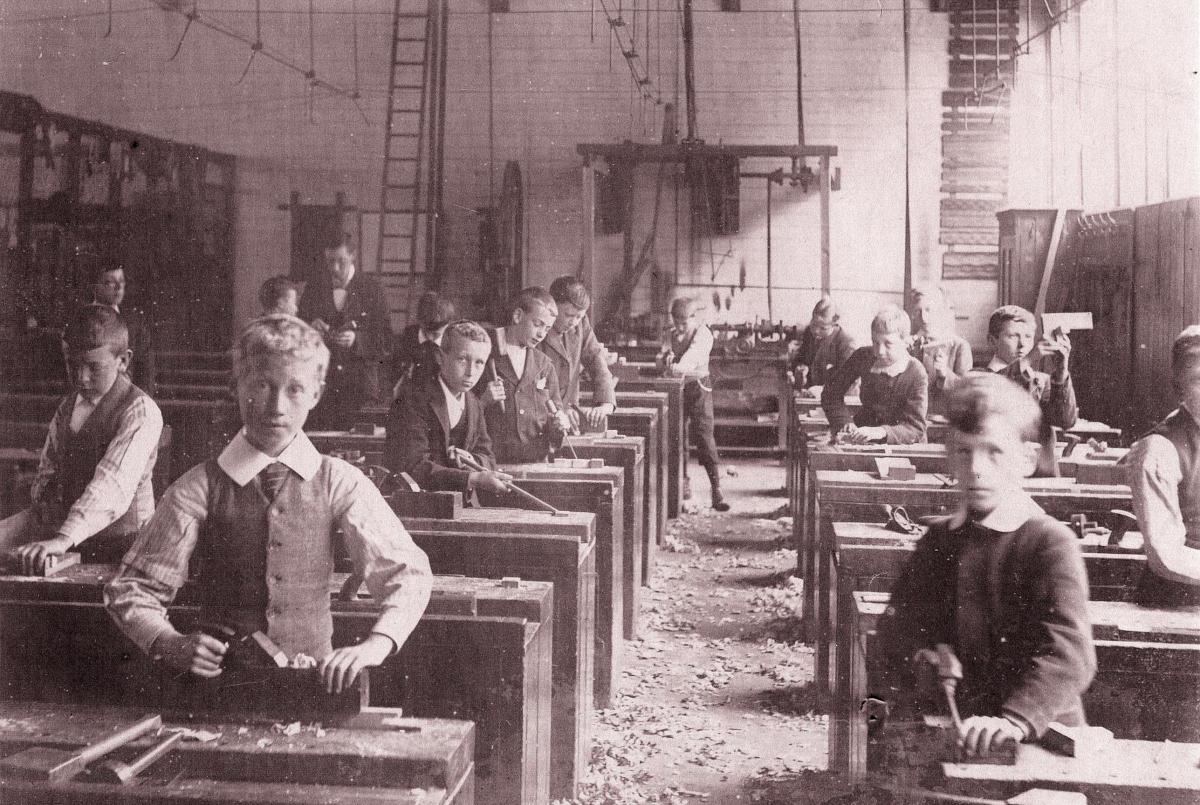

Hugh attended Keighley Trade and Grammar School where he showed an aptitude for metal crafts.

In 1911 he gained a scholarship to study metalworking at the Royal College, where his uncle, the Silsden-born artist Augustus Spencer was the Principal.

From the start, Hugh’s artistic ability and inventiveness were noted by his tutors, particularly when working with iron.

In June 1914 he gained a Royal College design diploma and the College gave him a place to continue his studies to a more advanced level.

However, at the start of the war he joined the 7th (Service) Battalion, East Kent Regiment (the Buffs) and remained with them for his entire military service.

In June 1915 he married Doris Perkins, whom he had met in London, and one month later he was sent with his regiment to France. He quickly moved up the ranks to become a Sergeant and was recommended for officer training.

In 1917 he was commissioned as an officer and in August that year returned to his battalion as a Second Lieutenant. Before returning to France, Hugh had a brief period of leave with Doris and their child, a boy, was born in May the following year.

But Hugh never lived to see his son.

On October 12, 1917 the First Battle of Passchendaele began with the Buffs fighting alongside ANZAC troops, south-west of Poelcappelle.

Hugh was shot and killed on the first day of action.

It is not clear what happened to Hugh’s body at the time of his death, but ‘an unknown soldier’ was later identified as him and he is buried at the Poelcappelle British Cemetery, near Ypres, Belgium.

The second casualty of the war was Thomas Smith Shackleton. He was born in 1891 in Keighley.

His family, of mother Rachael, older sister, Mary, and father, a local coal merchant, also named Thomas, lived at Gladstone Street.

The two children lost their parents in quick succession to fatal illness. Thomas, the father, died in 1901, and mother Rachael a few years later in 1905.

The two teenage children stayed on in the family home caring for each other.

By the time of the 1911 census Mary was an assistant teacher and Thomas was an art student at Keighley Art College, having previously been a pupil at Keighley Grammar School.

In 1912 Thomas was accepted by the Royal College to study design with the aim of becoming an art teacher.

However, in 1914, at the start of the Great War he abandoned his art studies and enlisted as a Private with E company of the 6th Battalion of the West Riding Regiment. This was no sudden impulse though, as from 1910 he had been a volunteer with the regiment, based at Skipton.

From 1915 his fought with his battalion in France, including at the Battle of the Somme in 1916. He remained unscathed through these battles and rose through the ranks.

In December 1916 he returned to England for officer training and gained his commission as a Second Lieutenant.

In March 1917 Thomas returned to France to serve as an officer with the West Riding Regiment.

In a joint operation with Australian troops, the regiment attempted to capture Bullecourt, a village bordered by the German defensive Hindenburg Line.

They met with fierce resistance, and on May 5, 1917 Thomas was killed by a shell. He is buried at Ecoust Military Cemetery, France.

The third artist, George Frederick Demaine, was also a casualty of the war, but in a very different way.

He was born 1892 in Keighley and he and his parents were committed members of the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel in Fell Lane.

George studied art initially at Keighley College of Art and gained a scholarship to study sculpture at the Royal College.

He joined the Royal College Christian Union and, to indicate his opposition to the 1914-18 war, also joined the NCF: No-Conscription Fellowship.

But in 1916 George was called-up to serve in the armed forces. He duly appeared before Chelsea Military Service Tribunal and claimed exemption on the grounds of his religious beliefs and objection to war.

He was one of 16,000 men in Britain who claimed exemption from military service during the 1914-18 war on the grounds of conscientious objection.

However, very few were granted full exemption and many accepted non-combatant roles.

Predictably, the Chelsea Tribunal only allowed George exemption from combatant military service and he was deemed liable for call-up to the Non-Combatant Corps.

However, George was an ‘Absolutist’ - renouncing any work that assisted the war effort. He subsequently refused to comply with a notice to report for military training and on May 16, 1916 was arrested by the civil police.

He was taken before the Chelsea Magistrates’ Court, pleaded not guilty, and submitted that as a Christian he could take no part in warfare.

It was reported in the press at the time that he had argued: “The only force which the Bible recognised was the force of love, which sought to save men and not destroy them.

“Therefore, he humbly but firmly stated that could not, under any circumstances, become part of a military machine the object of which was to destroy life. “

George was convicted and taken to an army depot in East London, where he disobeyed a military order. On May 30, 1916 he faced a court-martial and was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment, later commuted to 112 days imprisonment with hard labour.

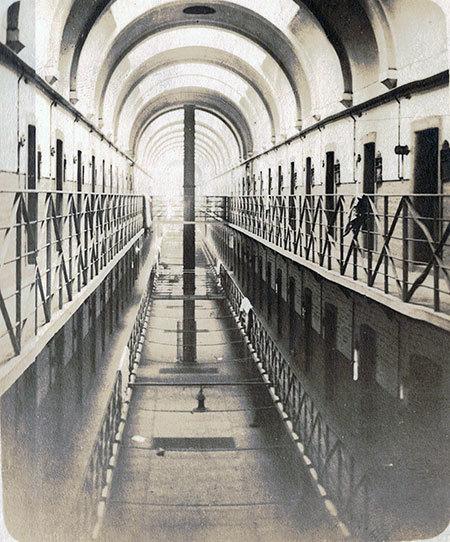

He began his sentence in Lewes Prison, but was later transferred to Wormwood Scrubs, London, prior to his appearance at a Central Tribunal in London.

George appeared before the Central Tribunal on August 16, 1916, where he was redefined as a ‘genuine’ Conscientious Objector, and offered work of national importance under a government scheme introduced earlier that year.

But he still refused to comply, so on his release from prison was sent back to the army. In December 1916, he again disobeyed an order and was court-martialled and sentenced to another 112 days imprisonment with hard labour, which he served in Mountjoy Prison, Dublin.

Hard labour meant long hours of manual work, often breaking stones into gravel or stitching mailbags.

Nearly 6,000 Conscientious Objectors served prison and work camp sentences in Britain during the F First World War, and over 70 died of ill-health attributed to the harsh treatment received there.

On his release in 1917, George was transferred to Arbour Hill Barracks, Dublin, where he again disobeyed military orders, had a third court-martial, and was sentenced to a further one year imprisonment with hard labour, served again in Mountjoy Prison.

The cat-and-mouse cycle continued with release, then a fourth court-martial at Dublin on March 7, 1918 for disobedience, resulting this time in two years’ imprisonment, served in Walton and Wakefield Prisons.

He was finally released on April 16, 9 having served nearly three years in prison with hard labour.

On his release he returned to the Royal College of Art and completed his studies in 1921.

He went on to become a sculptor and landscape artist, exhibiting work at shows of the Royal Academy, Royal West of England Academy, Alpine Club Gallery, and locally at Cartwright Hall, Bradford.

He died at Dover, Kent, in 1966.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here