Here, Robin Longbottom examines how mills produced their own gas to provide lighting after the use of candles came to an end

FROM the very onset of the Industrial Revolution, mills operated 24 hours a day for six days a week.

In the 18th and early 19th centuries during the hours of darkness, candles were the main source of light and huge quantities were required.

This form of lighting brought its own dangers and mill fires were not uncommon. The most notorious was at Colne Bridge, near Huddersfield, in 1818 when seventeen girls aged from nine to 18 years old lost their lives in a fire thought to have been caused by a candle falling over.

However, new developments in the manufacture of gas resulted in mills turning to gas lighting during the 1820s and 1830s. It not only provided a more consistent light but also proved to be a lot safer. The only downside to adopting gas lighting was that mills had to make their own gas.

Gas was manufactured from coal in what was known as a retort house.

Here the coal was packed by hand into a retort – which was a long, airtight, horizontal oven with a door at one end.

The oven was heated to a very high temperature by a fire lit below it and as the coal was ‘cooked’ it gave off gas that was then piped away, cooled and stored in a gas holder, more commonly referred to as a gasometer.

Once all the gases had been burned-off, the heated coal – known as coke – was then raked out by hand and this could be burned again in the mill’s boiler house, or sold off. Although it was harder to ignite than coal, coke was much sought after, particularly for heating blast furnaces in the local iron foundries.

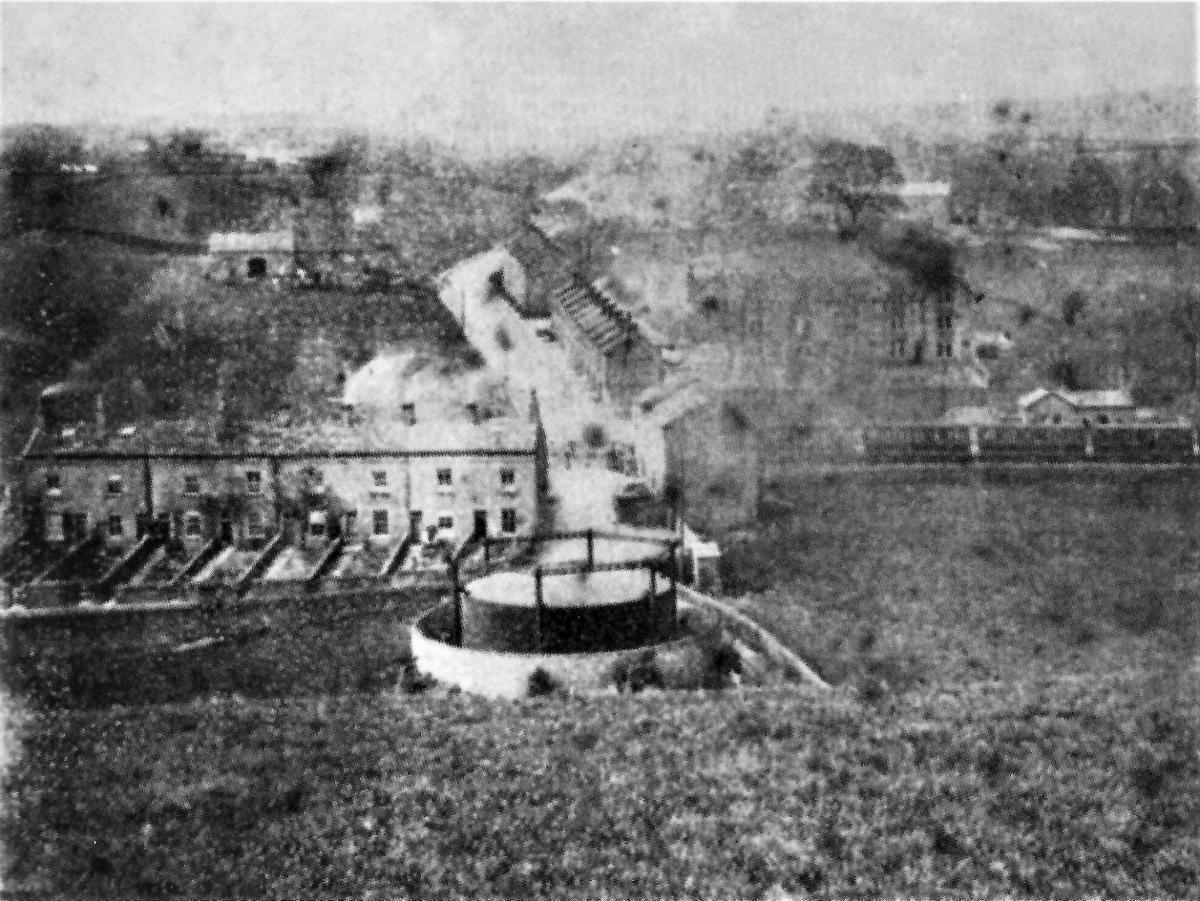

Few examples of a retort house survive today. However, one has been preserved at Woodlands Mill in Steeton and is complete with its chimney. It has now been converted into a dwelling. The gas that it produced was sufficient to light the entire four-storey mill and all its ancillary buildings.

When the gas had been made it was stored in a gas holder that could expand up and down to accommodate it. None of the once-many mill gas holders have survived, although the site of one that stood near Griffe Mill at Stanbury is still evident from the remaining circular stone wall that once surrounded it.

From the gas holder the gas was distributed throughout the mill in lead pipes. Numerous spurrs branched off from these pipes and led to the gas burners that produced the light. Until 1895, when the gauze gas mantle was invented, they were just open flames not dissimilar to a school Bunsen burner. Protection against fire was provided by a glass globe, or lantern.

Some mills such as Vale Mill at Oakworth produced enough gas to require two gas holders. One was situated in the yard at the rear of the mill and the other some distance away towards the bottom of Station Road. It is likely that Oakworth Station took its first gas supply from Vale Mill.

The development of the electric light towards the end of the 19th century brought an abrupt end to gaslighting in mills, although a few gas lamps in public streets remained into the 1950s.

Today gas lights are very much a thing of the past, however the soft, mellow light that emanates from them can still be experienced locally at stations along the Keighley and Worth Valley Railway line. The preservation society is said to be the largest remaining consumer of gas for lighting purposes in the country.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here