Here, Robin Longbottom examines one man’s extraordinary life and why questions were sparked by the award of a knighthood

WHEN Henry Isaac Butterfield – the creator of Cliffe Castle in Keighley – died in 1910, his personal and real estate was inherited by his son Frederick Butterfield.

Born in Paris in 1858, he was named Frederick William Louis d’Hilliers Roosevelt Theodore. Frederick William was after two uncles, Louis after Louis Napoleon Bonaparte (Napoleon III), d’Hilliers after a Marshall of France, and Roosevelt Theodore after Roosevelt relatives in America (he insisted that Theodore Roosevelt, president of the United States, was his first cousin despite their common ancestor having died five generations back, in 1724).

Known to the family as Louis, he spent much of his childhood at Cliffe Hall in the care of his maiden aunt, Sarah Hannah Butterfield. In later years he lamented that he hadn’t had a first-rate education because “my father had no love of letters and hardly ever opened a serious book”.

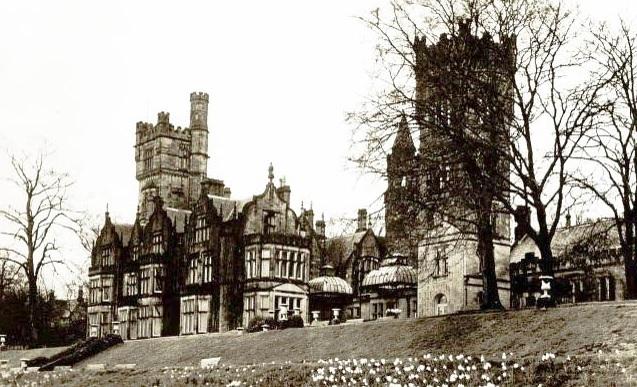

Having inherited a “little fortune” from his maternal grandmother, he went to New York and studied law. He graduated in 1882 but never practised. Instead he enrolled at the Leipzig Conservatoire in Germany, where he studied the piano for three years. After his musical interlude he returned to Cliffe Hall, now transformed by his father into Cliffe Castle.

Here he met a young American, Jessie Kennedy Ridgway, who was touring Europe with her parents. They were married in Philadelphia in 1888 and he entered the diplomatic service and was appointed American consul in Ghent, Belgium.

His sojourn in Ghent was short – he resigned as consul in 1890 then left for England before going to New York. In 1893 he returned to Keighley, having concerns that his ageing father may “leave his money outside the family’’.

Once affairs with his father were settled, he enrolled at Balliol College, Oxford, and studied Anglo-Saxon and Medieval English. He left in 1905, having attained an MA.

He was living in Paris when his father died and on his return to England inherited Cliffe Castle, a house in Paris, one in Nice, one in Teignmouth in Devon, the hamlet of Lumbfoot with a tenanted mill, another tenanted mill at Ingrow and Jubilee Tower and Farm in Steeton – a total fortune of £250,000, worth approximately £20 million in today’s money.

In 1911 he was invited to stand as Conservative candidate for Keighley but had to decline as he was an American citizen.

Keen to enter politics he took British citizenship in 1912 and the same year was prospective candidate for Shipley, where he made a speech supporting women’s suffrage – suggesting that their voting age be fixed at 45. However, he never achieved his ambition to become a member of parliament.

With impending war in Europe, he sold both houses in France and bought one in London. And after the outbreak of war, he donned a military uniform and became the Military Representative for Denholme, where he recruited men for the army.

He then turned to local politics, resigned from the ‘army’ and was elected mayor of Keighley in November 1916, serving two terms during the Great War.

He was rewarded for his public and civic services by Lloyd George, Britain’s wartime Liberal Prime Minister, and granted a knighthood in 1922.

However, the honour was rather overshadowed by the revelation that Lloyd George had been selling honours to raise money for party funds (a knighthood could be acquired for £10,000). The scandal ended Lloyd George’s political career and rumours about Frederick Butterfield’s knighthood rumbled on in Keighley long after his death.

Frederick’s wife died in 1929 and in 1930 he married Hilda Walters, a wealthy American widow.

He died in 1943, having enjoyed a privileged life beyond the imagination of the men, women and children who had spent their lives toiling in the Butterfield family mills.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel