Robin Longbottom examines how stone from a village quarry was much in demand, particularly from across the Atlantic

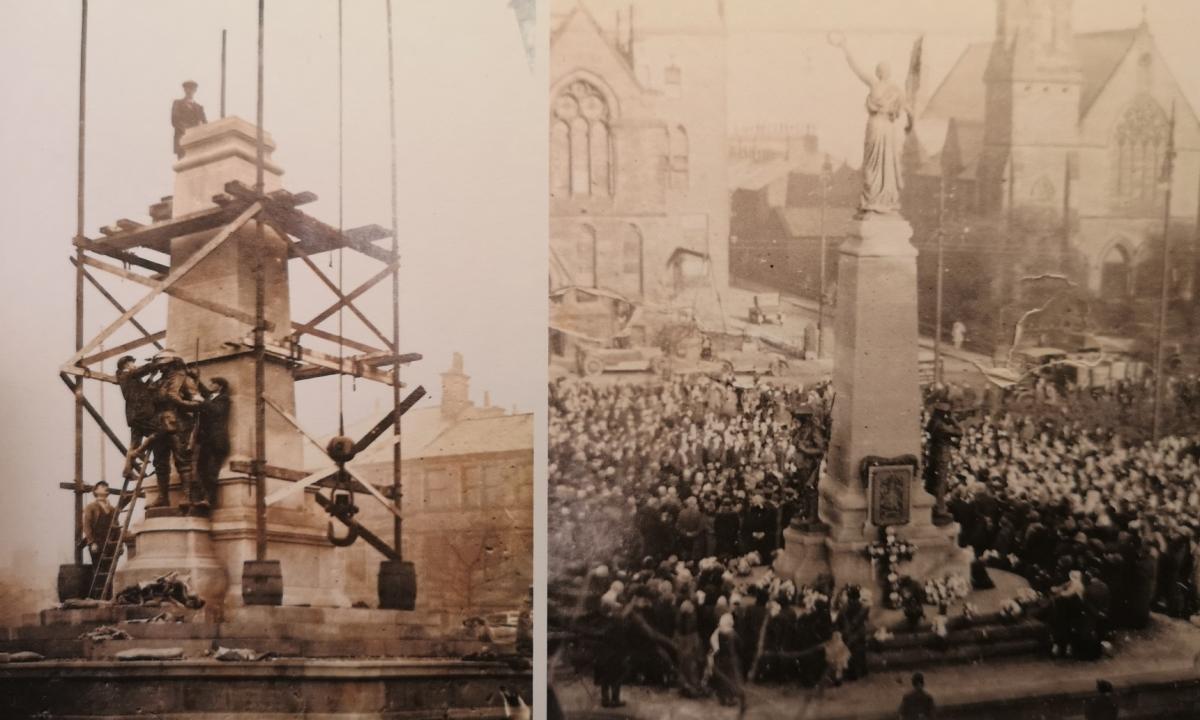

ON December 7, 1924, the ceremony took place for the unveiling and dedication of the Keighley war memorial.

The monument was designed by Henry Charles Fehr, a monumental and architectural sculptor.

Unlike many war memorials that were made of white Portland stone, the one in Keighley was made from local gritstone.

It was reported that the structure contained “something approaching 200 tons of solid masonry, all the stone being from the famous Eastburn quarries”. Although the stone from Eastburn was keenly sought by local builders, it was from across the Atlantic that there was the most demand for it.

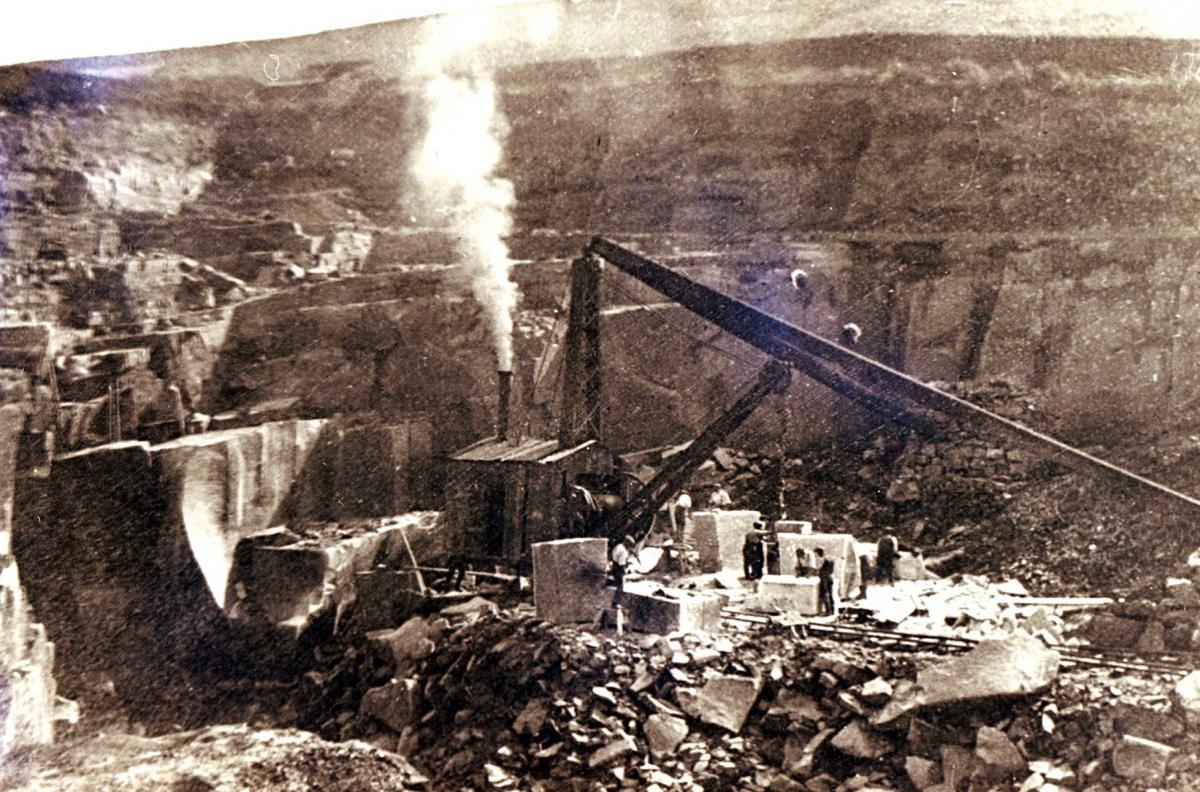

Eastburn Quarry had been opened in the 1890s by Thomas Atkinson, a builder in the village. It was noted for producing fine ashlar gritstone. However, prior to the outbreak of the Great War, a deep bed of very fine quality gritstone was found, and this came to the notice of American agents for the wood pulp industry.

Paper had been made from linen and cotton rags for centuries but at the beginning of the 19th century a process to make it from wood pulp had been developed in Germany. By 1850 the Americans were making paper from wood, particularly for the rising newspaper industry. To make the paper, revolving millstones – known as pulpstones – were used to grind the wood into pulp. However, the texture of the stones had to be so fine that it would wear down evenly and produce the long, slender fibres that were required. The finest quality gritstone from the north of England proved to be ideal for this process and the first English pulpstones were produced and exported from the north east in the 1890s, known as ‘Newcastle stones’. By the 1900s suitable gritstone was also found in Derbyshire and then discovered in Eastburn.

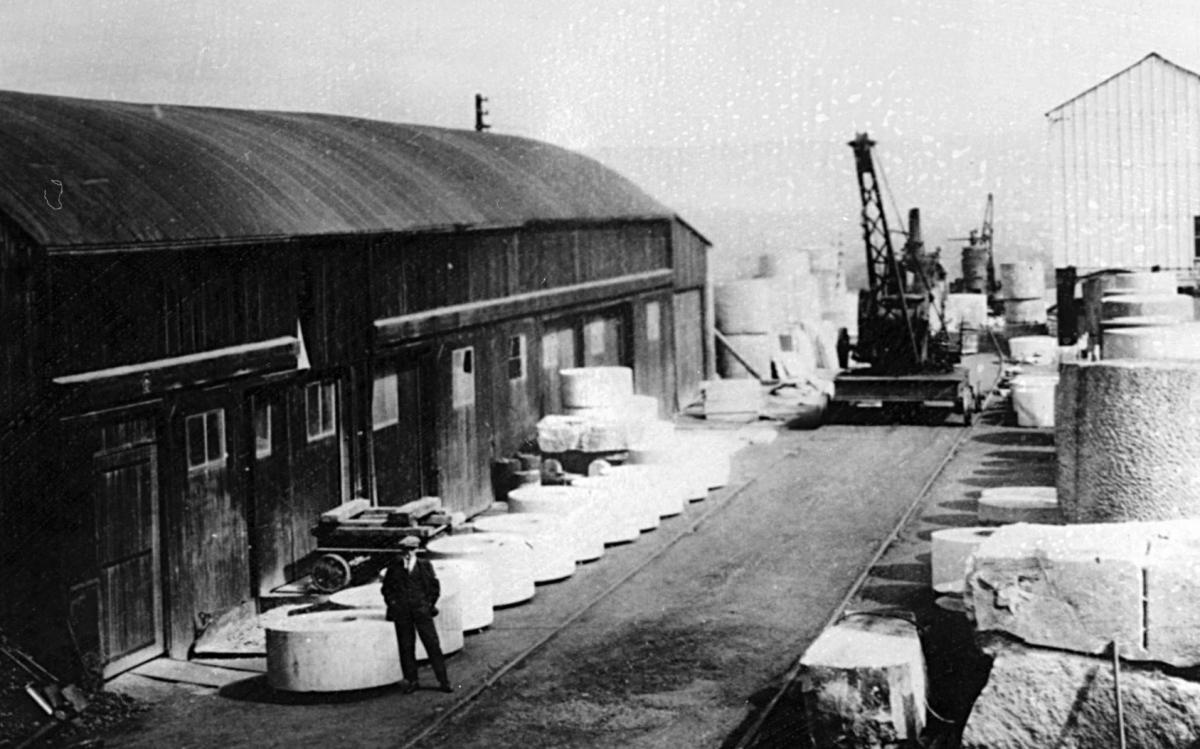

To make pulpstones, the Eastburn quarrymen first cut huge square blocks from the bedrock using hammers and wedges. The blocks were then taken to the dressing shed where masons, known as scapplers, roughed out the pulpstones – first cutting off the corners or spelshes (many of which finished up in garden rockeries), and then skilled masons finished the stones by hand. Two sizes of stones were made; the smallest were said to have weighed two-and-a-half tons, and the largest five tons. As the fresh stones were full of water, known as quarry sap, they were stacked and allowed to dry out for 12 months prior to being exported.

Before the outbreak of war, the first Eastburn pulpstones were quarried by Richard Calvert for an American firm called Lombard & Co of Boston, Massachusetts, and it was to maintain an interest in the quarry until the stone ran out. Lombard specialised in importing pulpstones for the paper industry in West Virginia and Ohio. The stones bound for West Virginia were imported through Baltimore on the east coast but those for Ohio had a longer journey along the St Lawrence Seaway and through the Great Lakes to Cleveland on Lake Erie. It is said that they travelled free, as they were used for ballast in the ships.

Following the end of the war, the quarry was run by Richard Dixon – a quarry merchant from Cononley – and he improved and developed the site. In 1919 he purchased railway lines and built an inclined trackway to bring stone down from the quarry to the workshops. He also built two trackways at the quarry for travelling cranes and another alongside the workshops. When electricity was taken along the Aire Valley to Skipton in 1920, Dixon applied for a supply to Eastburn and the quarry. He was then able to introduce electric power saws and tools.

By 1938 the quarry was exhausted and Eastburn’s export of pulpstones to America finally came to an end.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel