Robin Longbottom examines how three very different steam engines, which once powered our mills, have been preserved

THE abundance of water as a source of power sparked off industrialisation in Keighley and South Craven, but after the turn of the 18th century mills and factories began looking to steam power.

Initially steam engines were a secondary source of power and used in times of drought, or in harsh winters when mill wheels were frozen up. However, as engines became more reliable, many mills abandoned water power and turned to steam.

For over a hundred years steam power was king, however, with the introduction of the electric motor in the 20th century, its fate too was sealed.

After the Second World War, engines were being scrapped in huge numbers as electric power took over. Today steam power, like the waterwheel, is confined to history but remarkably three very different engines from South Craven mills have survived to the present day, two in museums and one still in the mill that it once served.

The oldest of these engines is a 150-horsepower beam engine, built by Burnley Iron Works Co in 1865. The basic design had changed little since the days of Newcomen and Watt in the 18th century. It had a vertical piston with a connecting rod that forced one end of an overhead, pivoted, beam up and down. A second connecting rod at the other end of the beam converted the vertical motion to a horizontal one, via a crank, to drive line shafting in mills. The engine was built for Eastburn Mill and ran for EA Matthews & Co worsted manufacturers, in Eastburn, until the 1970s. It was dismantled and removed to Bradford Industrial Museum at Moorside Mill in Eccleshill, and although work started on rebuilding it, the project still hasn’t been completed. Nevertheless, it is preserved, and the potential remains for it to be fully restored.

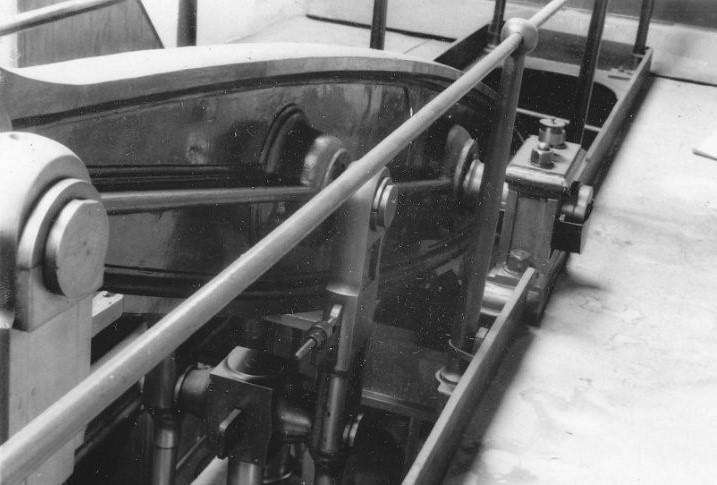

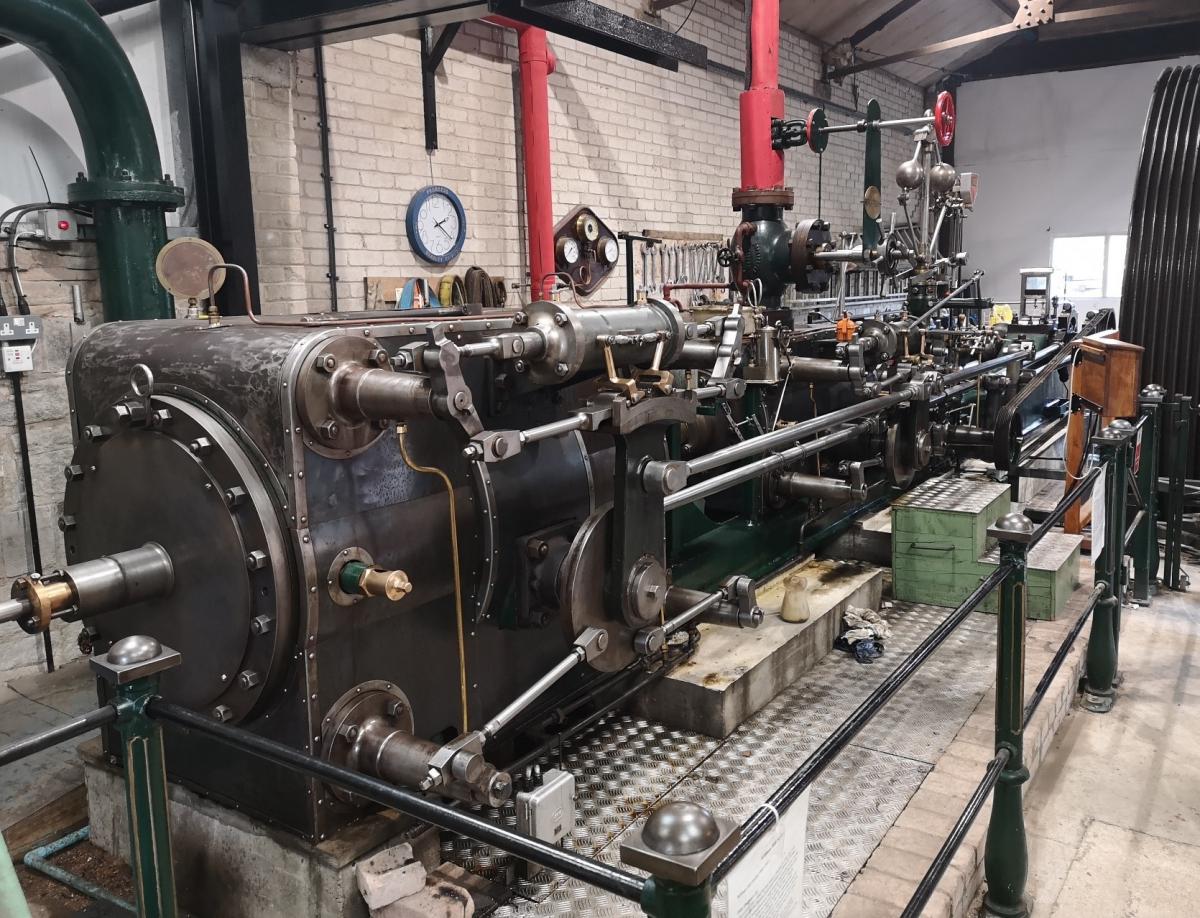

The second engine is a horizontal steam engine. Here the cylinder, piston and connecting rod are all horizontal. These engines are long and low and unlike a beam engine did not require a tall engine house. This engine was built in 1901 by Smith Bros & Eastwood of Bradford for Peter Green and Co Ltd of Cross Lane Mill, Bradley. It replaced a beam engine and powered worsted spinning frames in the mill. It ran until about 1978 and is now preserved at Bancroft Mill Engine Museum in Barnoldswick and can be seen running on special steaming days between March and November.

The last engine is a vertical steam engine and is said to be the largest one remaining in the country. It is almost three storeys high in the engine house that was built for it at Waterloo Mill in Silsden. It has a vertical cylinder and piston that stands above the connecting rod and crank and is more particularly described as an inverted vertical engine. It is a huge 700-horsepower engine built by Scott & Hodgson of Guide Bridge, Manchester, in 1905. It was made for J&W Hamer, cotton spinners, of Union Mill, Guide Bridge, but in 1915 the mill burned down. However, the engine was in a separate building and survived the fire. In 1916 it was bought by Waterloo Mill and dismantled in 1917 and transported to Silsden by barge. Fortunately, both mills stood at the side of a canal, the Union Mill on the Ashton Canal and Waterloo on the Leeds and Liverpool Canal, both canals were connected, and the engine was transported on the network via Manchester and Wigan to Silsden. The engine ran until 1978 and has a massive 18-foot-diameter flywheel that held 18 cotton ropes, which powered spinning frames and looms throughout the mill.

These magnificent engines are now preserved and a legacy of our region’s once rich industrial past.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel