Robin Longbottom on how a dynasty of millwrights stretching back five generations made its mark on industry in the area

WHEN Walter Barrett died aged 52 at his home in Station Road, Cross Hills, in 1912, he was the last of a dynasty of millwrights that stretched back five generations to the middle of the 18th century.

The Barrett's were already a long-established family in Sutton-in-Craven when Thomas Barrett, a carpenter by trade, turned his hand to building waterwheels, shafts and gearing. He is first recorded in 1760 by Jeremy Carrodus, the manor bailiff for the 4th Duke of Devonshire in Keighley. Carrodus was overseeing work to repair the manorial corn mill and Thomas Barrett had submitted an estimate to repair the two waterwheels and the associated gearing. The estimate for the work came to a total of £37 and Carrodus wrote to the duke to support it, informing him that Barrett was “a mill right and had Rought at the mills maney ayear and knows them better than aney other person”.

Both of Thomas Barrett’s sons, Stephen and Peter, followed their father into the trade. In the early 1800s they put a waterwheel in a new cotton mill at Sutton. The wheel was put up for sale in 1844 and described as being 15 feet in diameter, six feet wide with an iron axle tree and malleable iron bucket covers. Peter Barrett continued the business after the death of his elder brother in 1825 and in 1837 is recorded as installing a new waterwheel at Grove Mill in Ingrow. This was a 'state-of-the-art' suspension wheel, 20 feet in diameter, 12 feet wide and constructed with 18 wrought iron arms, or spokes, and 18 adjustable wrought iron cross braces to keep the wheel running true.

In the late 1840s Barrett’s relocated from Sutton to Eastburn where they probably took room and power at Eastburn Mill. After Peter Barrett died in 1847 the business was run by his brother Stephen’s son, who was also called Stephen. By 1851 the firm was employing 24 men and boys and in need of larger premises, so a plot of land near Eastburn Bridge was purchased. A new foundry, forge and works were built. The land had the benefit of a mill stream which was harnessed to drive a small waterwheel to power trip hammers in the forge.

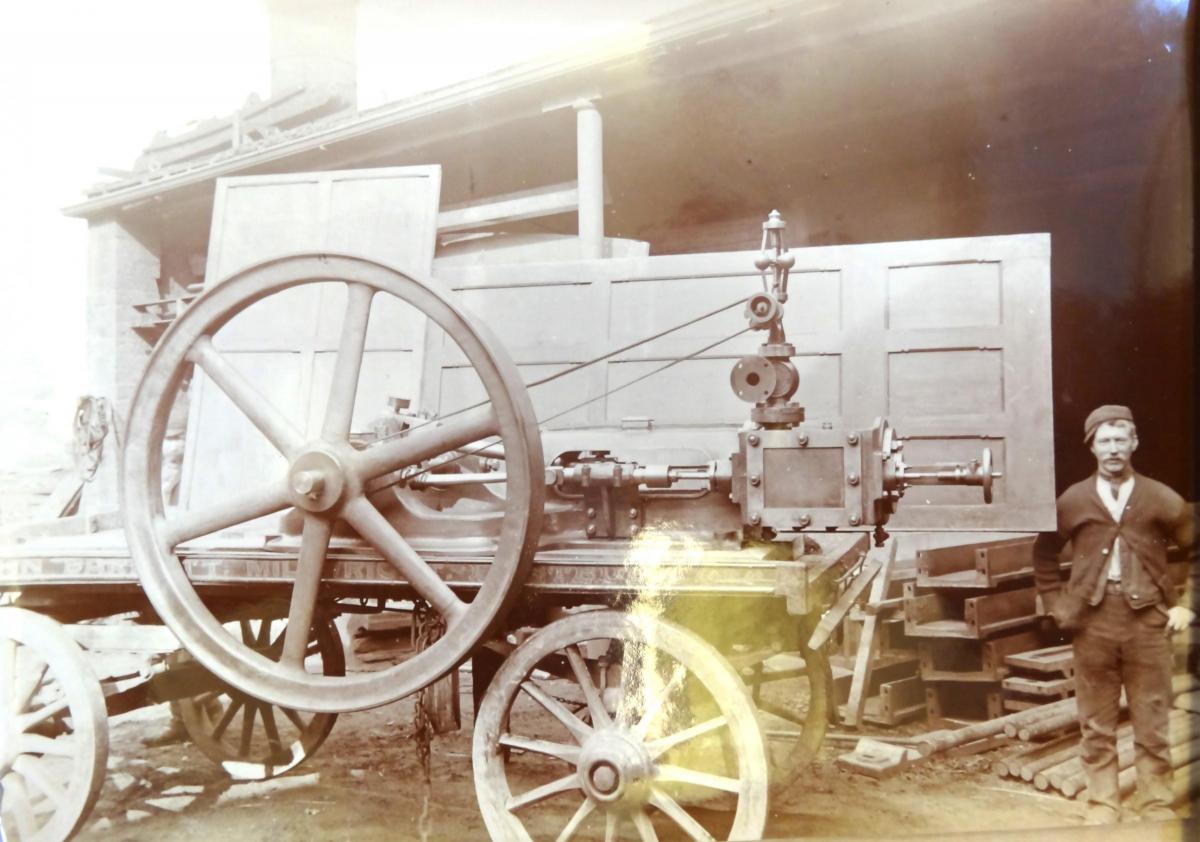

Under the later direction of Stephen’s son, John, the business expanded rapidly. In the 1870s they began making Corliss stationary engines, developed by an American called George Henry Corliss. These steam engines were up to 30 per cent more efficient than a conventional engine and were used to drive line shafting in small workshops and dynamos to provide electric lighting. The firm also manufactured hydraulic pumps for mines, air and circulating pumps and hoists for multi-storey mills.

However, the core business was still making and maintaining waterwheels and general mill work. They were renowned for their heavy castings, particularly bevel and mortice wheels used to convert vertical drives to horizontal shafting. The firm also made pedestals and hangers that supported line shafting to transmit power to machinery.

Walter Barrett was the fifth and last generation of millwrights and had taken over the management of the business from his father, John, in 1882. The works then employed 45 to 50 men and extended over an acre of land. Like most industrialists at the time the Barrett's lived in a large detached house on the site.

In about 1904 and probably due to ill health, Walter Barrett sold the business to John Lund, a Keighley mechanic and machine maker born in Oakworth. Lund continued the foundry and making mainly castings and lamp standards for the gas industry. The business was subsequently taken over by Clapham Brothers of Keighley and in 1958 it became part of the America-based Landis Tool Company.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here