Robin Longbottom examines the growth of the clogs industry as the footwear became hugely popular

UNTIL the mid 14th century, England’s wealth came from the export of wool to the continent.

However, Edward III (1327-1377) encouraged Flemish weavers to settle in England to establish a home manufacturing industry.

These immigrants are said to have brought with them “wode shoon all of a peece” (wooden shoes made in one piece) and so introduced the clog. Whether or not this was the case remains unknown, but by the late medieval period clogs were so popular that a law had been passed forbidding them to be made from poplar, which was reserved for making arrows.

Eventually making clogs from a single piece of wood was abandoned and two-piece ones with a leather upper were made. Clogs were subsequently worn throughout the British Isles, from the Channel Islands to Ireland and the north of Scotland, until the 1940s.

Alder was the principal wood of choice for soles and large stands of trees were purchased, particularly in Wales and Ireland. Men known as clog blockers set up camp onsite and remained throughout the summer, cutting the timber into lengths, splitting it and roughing out clog soles with large stock knives. The soles were then stacked to dry before being sold on to clog makers.

The tanning industry also catered for clog makers and produced a specialised leather known as kip. This was heavily impregnated with wax, making it both waterproof and highly durable. The manufacture of clog nails and caulkers, or clog irons, also developed on an industrial scale, for which Silsden was once an important centre.

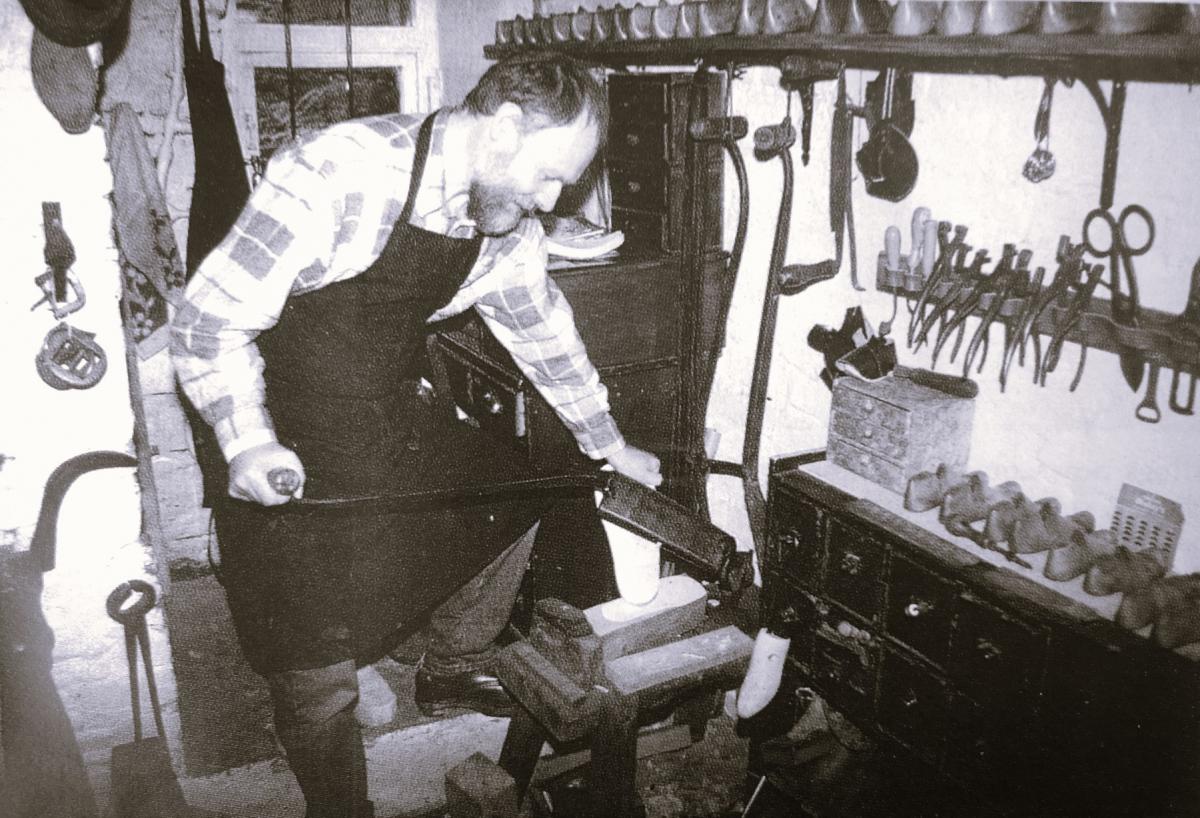

One of the last old-time clog makers in the area was Harry Greenwood, known as ‘Harry Bobwire’, who for many years had a shop at Cross Roads.

Born in 1902, he served his time with George Peacock, a boot and clog maker at 115 Main Street in Haworth. Harry set up his first shop in Lees, at the junction of Hebden Road and Haworth Road (it was demolished in the 1960s to improve the road junction), before moving up the street to Cross Roads.

In his early years he finished clog soles with stock knives, cutting out the hollow for the foot and the recess, or grip, for the upper. However, he later bought finished soles from Maud’s clog factory in Hebden Bridge. He also cut out uppers by hand until machine-stitched ones became more readily available. The uppers were fitted to the sole by stretching them over a wooden last. The process, known as ‘knocking up’, required the leather to be warmed to soften the wax, it was then moulded to the last using a long two-handled bar known as a boshing iron. Finally, it was then tacked into place and left to ‘set’.

Harry made a traditional Pennine clog known as a duck toe. The sole was extended at the toe and the exaggerated curve, known as the cast, gave the wearer the additional roll needed when walking up hills. Soles with a round toe were more common in the rest of the country but in mining areas a square toe was often preferred, as it enabled miners to balance when sitting on the heel and working.

By the 1920s, shoes and boots had become cheaper and began to replace clogs as footwear for work. In the West Riding and Lancashire, they continued to be worn outdoors into the 1950s and also in foundries and mines. However, contrary to popular belief, clogs were never allowed to be worn in mills as the clog irons would have severely damaged the wooden floors – after removing their clogs, old shoes were worn.

When Harry died in 1978 his son Ellis took over, assembling soles and uppers for the few clog wearers that remained. He retired in 1998.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel