Robin Longbottom examines how a surviving will and inventory provide a glimpse into home life over three centuries ago

ON January 3, 1714, Thomas Bottomley – a clothier and farmer of Jackfield, Sutton-in-Craven – made his last will and testament.

When he died that April, aged 76, his executors were required to make an inventory of all his goods and chattels and submit it together with the will to the Prerogative Court in York for a grant of probate.

Fortunately, the will and the inventory have survived the ravages of time and provide a window into the home and farm of a man who lived over 300 years ago.

Jackfield lies beyond the village on the hillside just below Sutton Pinnacle (Lund’s Tower) and is known today as High Jackfield. Built in the 17th century, the house and adjoining laithe, or barn, still retain many features of the original property.

Thomas Bottomley was born in Keighley in 1638 and at the rather advanced age, for the times, of 28 he married Ellenor Bracewell of Colne. He was a clothier, a trader who put out warp and weft to handloom weavers, paid them for their work and then took the woven cloth to sell at market. By 1670 the couple had settled at Jackfield where their eldest child was born; the property was leased and lay conveniently between both their home towns.

The house had two ground-floor rooms and two rooms upstairs. On the ground floor was the housebody (the main living room) and the parlour. The most important feature in the housebody was the fireplace. To one side of it was a cooking range with a backstone, or griddle plate, for making oatcake (unleavened flat bread). Hung above the open fire, from inside the chimney, was a reckon, a large adjustable hook to hang a cooking pot on. There was also a set of tongs to mend the fire. Most food would have been cooked in the calepot, a large cauldron used for cooking cale, or stew, that was the staple meal in the area. There were also several cooking pans to make lighter meals and preserves. The furniture in the room included a wall rack to hold the family’s plates and dishes, seven chairs with cushions and a little table.

The parlour was the couple’s private room. It was where they slept and in it was a bed, a table, and a box for storing linen. Ellenor would have entertained friends and visitors here.

Upstairs were two chambers. In the first room was a bed and bed linen, a large meal ark for storing oatmeal, four sacks and an old chest. In the other chamber was a half tester bed and bed linen, two old arks (large chests), some wooden vessels and sundry household goods.

The adjoining laithe provided shelter for the farm animals, a hay store and storage area for the farm equipment, including shears for clipping sheep, forks, shovels, axes and mattocks. When he died, Thomas had four oxen, two stirks (year-old cattle), one stott (young bullock), one heifer and 20 sheep. He had yokes and teams for his oxen and two ploughs and a harrow. There were also two cart bodies and one pair of wheels.

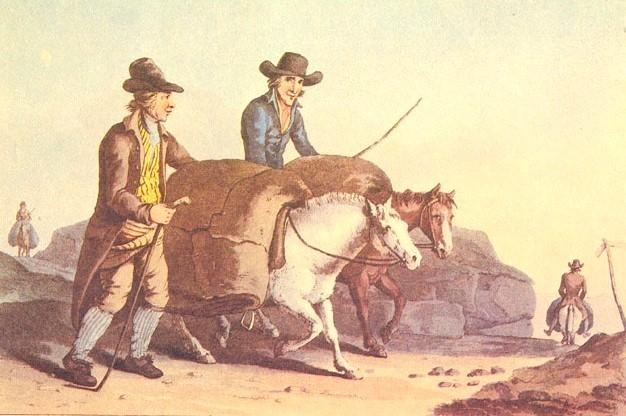

Finally, he had a horse, together with a riding saddle, bridle and pack saddle. The horse was essential for his business as a clothier, providing transport for him when he travelled around the district. It was also available for use as a packhorse when he was taking his cloth to market.

At his death his estate was valued at £50 7s 9d, about £100,000 in today's money. His wife and youngest son Christopher benefitted from the bulk of his estate. His son Thomas received £1 10s, whilst his other two children, William and Mary, were ‘cut off’ with a shilling each.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here