Robin Longbottom on how a horse-drawn secure waggon from Wales played its part in the construction of a Keighley railway tunnel

FOR almost a year, between 1878 and 1879, a horse-drawn waggon left Flint in north Wales every two months or so on a journey to Keighley.

It was a specially constructed, enclosed vehicle and before departing it was locked and the key posted to its destination to prevent anyone gaining access.

The journey took two-and-a-half days, travelling non-stop through the day and night. Relays of horses were stationed along the way at Chester, Warrington, Manchester, Middleton, Rochdale and Hebden Bridge. Under ordinary circumstances, goods would have been sent to Keighley by rail and arrive within the space of a day. However, the waggon carried two tons of dynamite and the railway companies refused to convey the explosive. The dynamite was required by contractors to the Great Northern Railway Company who were blasting out a tunnel under Lees Moor, near Keighley, for a new line to link Keighley and Halifax.

After years of planning, the project had been approved in 1873. The route was split into sections and tenders invited in January, 1874. The first section was from Keighley to Thornton and required two long tunnels. The tunnel at Well Heads, Thornton, was nearly half a mile in length. The rock here was a soft shale and so was dug out by hand. The Lees Moor tunnel was just short of a mile long and rose from Keighley at a gradient of one foot in every 50. Work here did not start until 1878 and was undertaken from the Keighley end to allow water to drain out. However, after only 50 yards they hit a bed of hard millstone grit and progress stopped.

To cut through the millstone, the contractors turned to the Diamond Rock Boring Company and its Beaumont Drill. The drill was powered by compressed air and fitted onto a carriage that ran on narrow gauge rails. It drilled four holes simultaneously to a depth of five feet and up to 24 holes were drilled into the rock at any one time.

Once the required number of holes had been completed, the machine was withdrawn and the “dynamite man” arrived “with a load of 30 pounds of dynamite on his back”. The first four holes were then cleaned out with wooden rods and the charge “well rammed without ‘flogging’ – that is to say without the use of hammers wherewith to strike the tamping rods". Explosive caps, each with six feet of fuse, were then fitted and the holes sealed with clay. The four fuses were lit simultaneously and “the men beat a hasty retreat”.

Once the dust had cleared, the “muck fillers” arrived to load the debris into a “train of waggons”. When all the debris had been removed, the process of charging another four holes began. After all the holes had been blown the drill was brought forward again and the process repeated. The work was arduous and “the men could only be induced to stick at their post by high wages and ample libations of coffee and rum”.

The tunnel advanced at a rate of about 30 yards a week and after almost a year, and ten tons of dynamite, they finally broke through to the Cullingworth end in October, 1879.

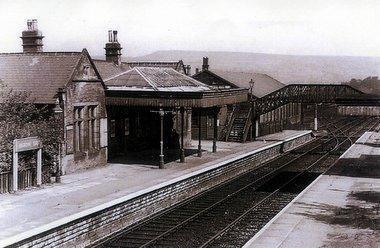

The line took nearly ten years to complete and opened to goods traffic in 1883 and to passenger traffic the following year. It had a junction with the Worth Valley line at Keighley and passengers left from the Worth Valley platform. A new station, Ingrow East, was built to cater for passengers from the Ingrow area. At one time it provided the quickest and most direct service from Keighley to Manchester and London.

The line closed to passenger traffic in 1955 and to goods traffic some years later.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here