Robin Longbottom looks at how increased demand for power looms led to change for many manufacturers

EARLY in 1822, “some gentlemen from Bradford” leased a room in a worsted mill in Shipley.

Here they were secretly developing a power loom to weave worsted cloth. However, on April 17, their secret got out, and a mob of handloom weavers broke into the mill and smashed up the machine. They then dragged the remains to Baildon where they ceremonially burned them.

In 1789 Edmund Cartwright, a Nottinghamshire vicar, had patented a mechanically powered loom but it only demonstrated the basic principles of a machine. Developing one that was practical for commercial use would be left to others, including the unknown “gentlemen from Bradford”.

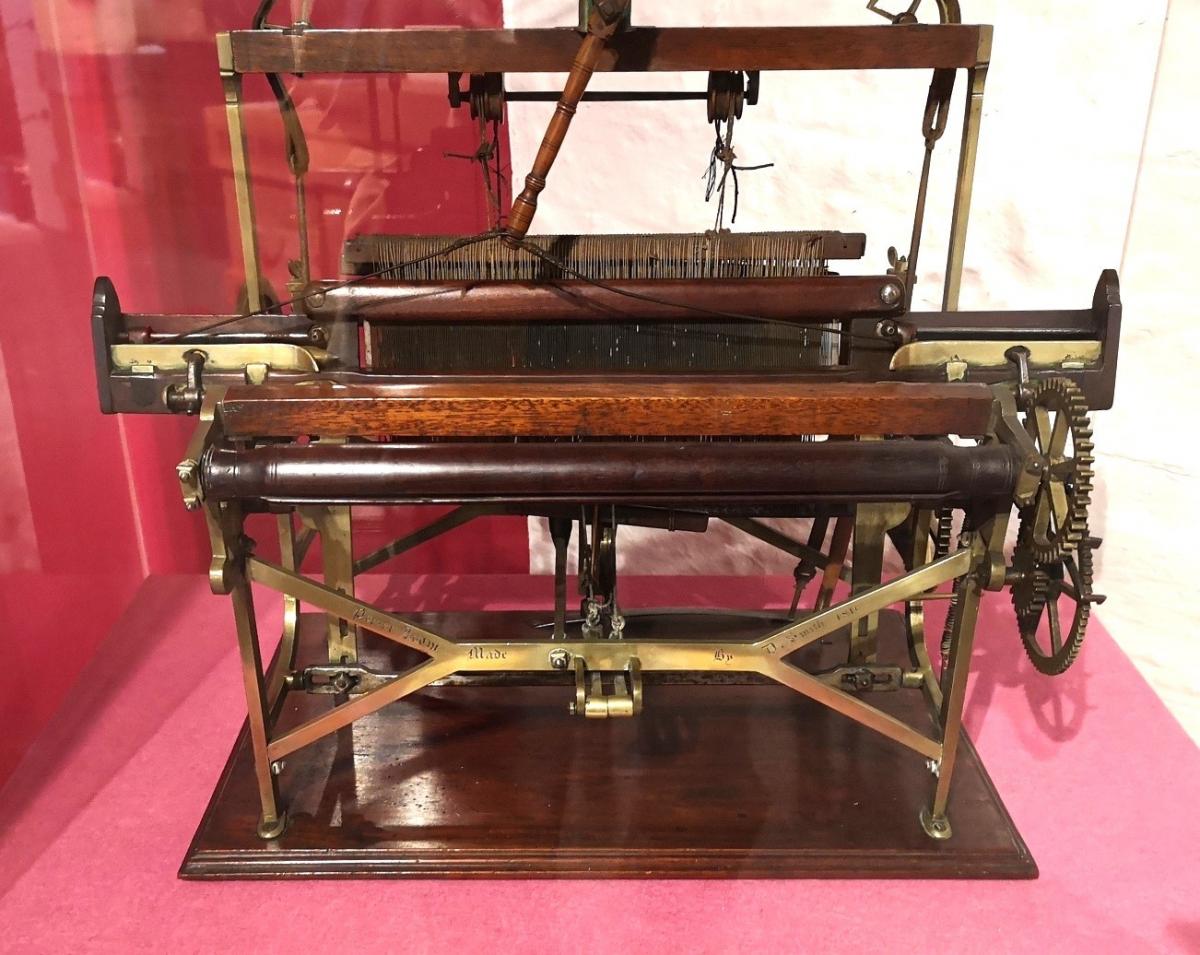

A power loom had to have a reliable and robust mechanism if it was to withstand the rigours of production both day and night for six days a week. A major problem to overcome was devising a mechanical method to propel the shuttle. Early power looms attempted to replicate the action of the ‘flying shuttle’, invented nearly a century earlier by John Kay. On a handloom the weaver yanked a central ‘picking stick’ attached to strong cords operating strikers that propelled the shuttle from right to left and back. In 1816 a mechanic called Daniel Smith made a working model of a loom that attempted to replicate this system. However, its central automatic picking stick and lengths of cord were unable to withstand the pounding inflicted by mechanical power.

The problem was finally solved by another clergyman, Richard Roberts, a Welshman living in Manchester. In 1822 he patented a power loom for weaving cotton which propelled the shuttle via two vertical levers. They were located at each side of the machine, just below the boxes that held the shuttles. This system was adapted by worsted machine makers who replaced the vertical levers with horizontally-operated picking sticks. They abandoned the use of cord and replaced it with a length of rawhide, a far more robust and reliable material. By the close of 1825 the press had reported that power weaving was “progressively increasing in Bradford and the neighbouring towns”.

To meet the increased demand for power looms, machine makers began to specialise in their manufacture. The first to do so in Keighley were Charles Fox and George Bland who worked from Acre Mill, off South Street. Fox was a whitesmith and Bland a blacksmith. They traded as Fox & Bland and were for many years the leading power loom manufacturers in the town, sending their looms as far away as Darlington. More locally they supplied 20 looms to Townhead Mill in Addingham in the mid 1830s.

Another partnership, John Longbottom & Company, began making power looms in Steeton from about 1833. This small firm was formed by three brothers, John, Charles and Matthew, all of whom were established machine makers and mechanics. They supplied power looms to many local manufacturers, including John Brigg at Brow End Mill, Goose Eye, and Thomas and Matthew Bairstow of Sutton Mill.

During the 1840s another partnership began to take an interest in the trade – George Hattersley, and his eldest son Richard Longden Hattersley. They had been manufacturers of rollers, spindles and flyers for spinning frames and of lathes for the machine tool industry.

Under the direction of Richard Longden Hattersley, the firm began to concentrate on making power looms. At the London Exhibition in 1862 they exhibited two new looms for weaving fancy cloth. They subsequently went on to make upwards of 20 different types of loom and their ‘standard’ broadloom was once the workhorse of the worsted manufacturing industry. They also made semi-automatic handlooms used to weave Harris tweed in the Outer Hebrides.

For over 120 years they were one of the country’s leading manufacturers of looms before finally closing in 1983.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here